The overall objective of the Sustaining Peace during Electoral Process (SELECT) project is to build the capacity of both national electoral stakeholders and international partners to: (a) identify risk factors that may affect elections; (b) design programmes and activities specifically aimed at preventing and reducing the risk of violence and (c) implement operations related to the electoral process in a conflict-sensitive manner.

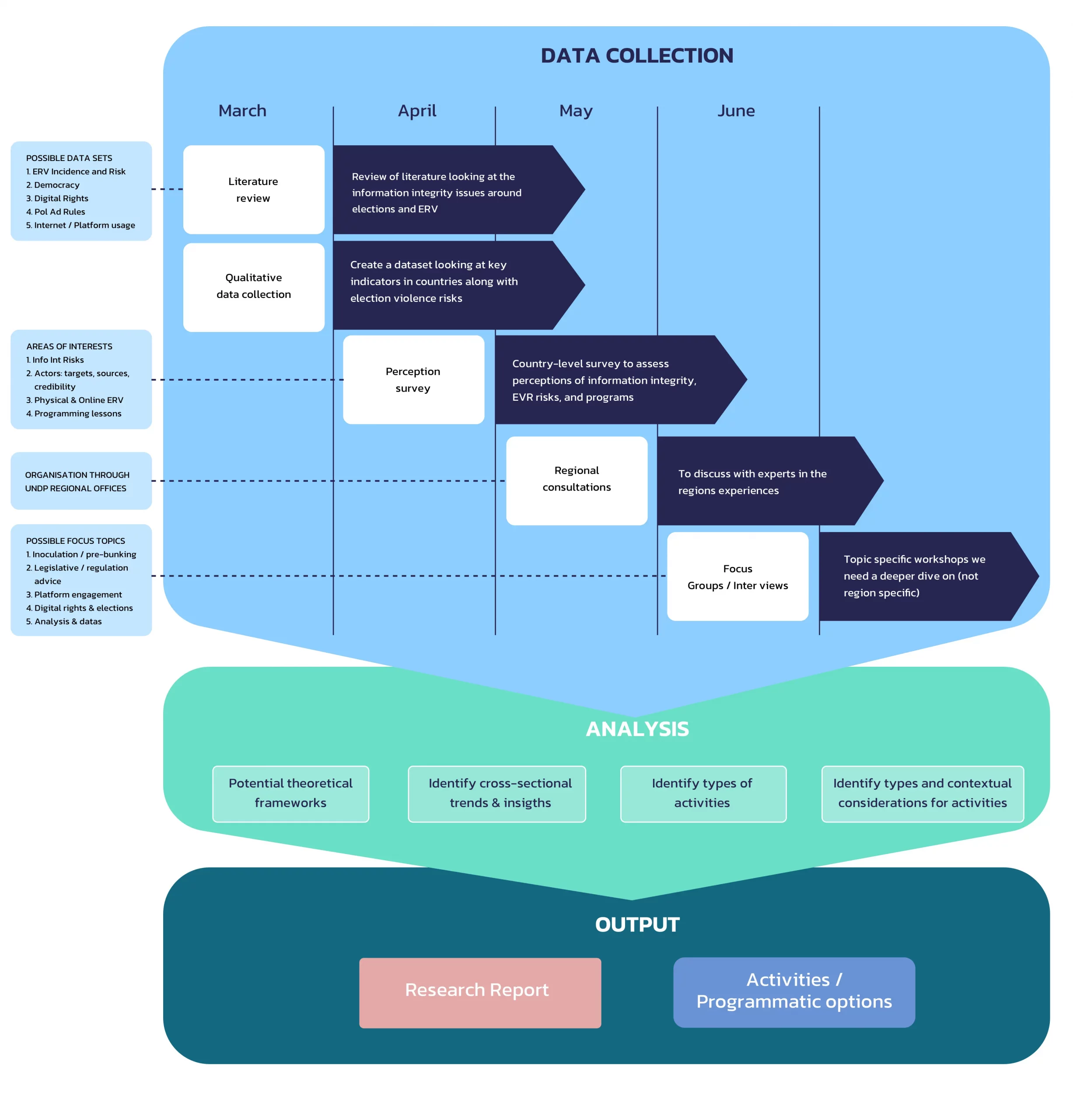

Against this background, the SELECT project has developed an inclusive research process to ensure a multi-regional lens that takes into consideration experiences and knowledge from a wide range of stakeholders. The research process will be applied to various research topics included in the SELECT project document whereby the topics identified have the potential to negatively contribute to or positively mitigate the potential for electoral violence. The aim of this topic-specific research process is to understand the main challenges in relation to the nexus between the topic and electoral violence and outline actionable solutions to be implemented in the second phase of the project. Any solutions presented are intended to be informative and not prescriptive, recognizing that each country context will be unique.

Each topic will be accompanied by a working group comprised of experts in the field and representatives of relevant organizations. The members of the working group shall share their experience and expertise, as well as support, with their networks. Participants of the working group and their organizations will be acknowledged for their contributions to the topic.

The outputs of this project will not constitute United Nations policy recommendations.

This report is dedicated to the first SELECT project research topic, which shall explore the prevention of election violence and its linkages to information integrity.

The advent of widespread Internet access and the evolution of social media platforms have created new networks connecting billions of humans across the world, changing the way people seek, share and are served information. In turn, new paradigms of communication have emerged and old trends have accelerated—transforming aspects of societies and economies. The flow of information through this evolving landscape is directed by a complex set of motivations and incentives, mediated through technology, socio-political conditions and user behaviour.

The Internet has become an inextricable part of modern political life. The benefits are potentially transformative, creating new and more egalitarian opportunities for involved parties to communicate and coordinate. The emergent social media platforms have been immensely disruptive to the conduct of elections and the ways by which political entities contest them—for better or worse. An early excitement has receded, replaced in the minds of many with concerns over the digital domain’s possible harmful impacts on politics, and democracy more broadly, with some wary that the risks may outweigh the benefits (United Nations, 2021).

The Internet provides a variety of transformative tools, which can be used for good or ill. It offers new means for citizens to reach each other, congregate, collaborate and evolve their common narratives. Social media arguably lowers the barrier to entry into political debate and opens the door to candidacy for those who had previously been excluded. Furthermore, the Internet provides an environment by which citizens can more easily access information about elections and politics.

Several deleterious effects of information pollution upon elections have been posited, including unduly influencing voters, defamation of opposition candidates, undermining the EMBs (Kimari, 2020), erosion of the credibility of the election process, impositions upon the right to participate in political affairs, gendered disinformation, online gender-based violence, heightened polarization and fomenting election-related violence. Certainly, these and related problems were present prior to the Internet. Yet, concerns are that new technologies are reinforcing these challenges and providing a toolkit for new impediments. The ultimate fear is the digital pathways have unique vulnerabilities that undermine the political norms, societal cohesion and voters’ free choice, all essential for democratic elections.

The opening of the digital space has created new vectors for electoral violence. Norms of civility are weaker online, with harassment of women, youth, minorities and other marginalized communities particularly prevalent and fast-growing (UN WOMEN, 2021) (Izsák-Ndiaye, 2021). Citizens and politicians alike find themselves subject to such abuse though some research suggests that incivility is not inextricable from online life, with a more polite environment potentially cultivated through design, policies and incentives (Antoci, Delfino, Paglieri, Panebianco, & Sabatini, 2016). With regards to women, specific concerns exist that they may be disproportionately targeted, facing narratives that can be used to portray them as unfit for public office, as villains or dismissed in other ways. This targeting is further accentuated for women of minority groups (Sobieraj, 2020).

Elections are by their nature sovereign exercises, making interference by external actors in domestic political processes deleterious to the credibility of the processes. Without publicly accepted protections, a borderless digital ecosystem may create damaging concerns of new avenues for foreign interests to target individual citizens or influence the narrative of the election.

The framing of this study is guided by the features of election-related violence. The United Nations Policy Directive on Preventing and Mitigating Election-Related Violence describes electoral processes as the methods of managing and determining political competition with the outcomes deciding a multitude of critical issues, leading to a highly competitive environment where underlying societal tensions and grievances may be exacerbated and ultimately may lead to electoral violence—a form of political violence that may be physical or take other forms of aggression, including coercion and intimidation (United Nations Department of Political Affairs, 2016). This can happen spontaneously or be planned by political actors and their supporters, the latter who may be paid to commit attacks against candidates of political opponents or to create violent scenarios that ultimately favour the sponsoring party. It may be staged to look like random attacks, organized to blackmail political candidates, involve kidnapping and be accompanied by acts of coercion, intimidation and threats (Opongo & Murithi, 2022). Findings indicate that election-related violence is typically conducted between competing parties (Ginty & John, 2022). While the focus of the research is on election violence—violence that is related to the holding of an election delineated by actors, timing and motives (Birch, Daxecker, & Höglund, 2020)—we remain cognizant that the tensions and disputes that may emerge from an electoral process may fuel subsequent political violence and diminish the legitimacy of governments.

This paper attempts to reflect the disputes around the ways and degree by which the concerns raised above actually emanate from the online space. Certainly, anxieties around election-related violence and propaganda pre-date the Internet—in one form or another. Laying the blame for the social ills seen over the recent past solely at the feet of social media could prevent the identification of other factors driving division and political unrest (Bruns, 2019). However, the digital age heralds new tools and novel dynamics—such as virality, velocity, anonymity, homophily, automation and transnational reach (Persily, 2019)—which indicate that it is not just more of the same. Certainly, the lived experiences of many of those that have been spoken to for the purpose of this research make it clear that there are indeed urgent and critical issues to address.

At the same time, there are great challenges in resolving these concerns, especially regarding elections. A fundamental question is, if elections require a free and pluralistic public debate, then on what basis are platforms, or even governments, censoring discourse? In the electoral context, perhaps the most straightforward type of information to combat is the immutable facts that define the process, for example, the dates within the electoral calendar of polling or eligibility requirements, as would emanate from the Election Management Body (EMB) or legislation. While confusion around such facts must be combatted, there is a myriad of other, more complex information pollution concerns to address.

There is an understandable differentiation between hate speech and other forms of information pollution. Hate speech is widely recognized within international human rights law as being prohibited, and established tests exist to define such content—notably the Rabat Plan of Action threshold (United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2013). In practice, there remain complex categorization and automation issues (MacAvaney, et al., 2019) (Van Zuylen-Wood, 2019). However, while these concerns are extremely serious, they are in some ways less contentious. In principle, disinformation calls for a different approach.

There is no common definition, understanding or approach to ‘disinformation’ within international human rights law. There are several tensions involved in tracking disinformation—or more broadly, information integrity. Rights to freedom of expression; the freedom to hold, form and change opinions; freedom of information; and the freedom to participate in public affairs, while in contention, are various protections that contribute to the legal guidance. Freedom of expression is not limited to truths; in fact, it especially does not preclude offensive and disturbing ideas and information, irrespective of the truth or falsehood of the content (Report of the Secretary-General, 2022). Despite these protections, reasonable exceptions in particular circumstances are provided for (United Nations, 1966). Where restrictions are in place, they are expected to meet a high threshold of legality, legitimacy, necessity and proportionality (Khan, 2021). The above vital protections simultaneously signal the limitations of content moderation as a solution to information pollution and demonstrate a need to look more broadly for solutions that are based in promoting international human rights law protections.

This paper also recognizes that the aforementioned United Nations Policy Directive on Preventing and Mitigating Election-Related Violence does not attempt to directly address information integrity issues. While this paper seeks to provide material to support programmatic activities, it does not form United Nations policy.

The study will explore the following questions:

It is beyond the scope of this exercise to provide definitive answers, but it rather aims to explore the questions to inform future programming. The report shall consider the existing research and marry this with insights from election practitioners across the world.

Ultimately, this report posits that strong information integrity is vital to ensuring credible and peaceful elections. Its exploration of the subject is towards an understanding of what the risks are, how information integrity environment may be achieved, and how this varies specific to the context.

There is limited rigorous research that focuses purely on the relationship between election-related violence and information integrity centered on the online experience. This is especially true outside of the Western experience. A broader set of literature exists enquiring about how information integrity influences election processes and public behaviour, though they rarely provide uncontested conclusions. Considering some key dimensions of the election process, the overview below seeks to illustrate the current debates and the research underpinning different positions.

Broadly, however, the current body of research describes digital media as posing benefits and risks to democracy. On the one hand, there is evidence that it can contribute to voter participation and mobilization. However, there are more mixed findings when it comes to political knowledge and concerns when it comes to trust.

The relationship between information pollution and elections is complex and at times counterintuitive. Some logical suppositions or popular narratives become confounded or diluted by evidence and empirical research. At the same time, the dynamic nature of the environment and data constraints contribute to difficulties in developing replicable studies, limiting the scope to test findings in new contexts.

It is important to keep in mind that investigation into this field of study continues at pace, and its findings are likely to evolve. It is also necessary to recognize the limitations of the current research, which is often centered on Western experiences and around the handful of companies willing to provide adequate datasets (Kubin & Sikorski, 2021).

There are a variety of ways to explore the ‘problem’ at hand. One is to consider how information pollution consumption influences voters in the context of an election process. Another is to explore the production and supply side of the election information pollution. The role of platforms as channels and actors in this relationship must also be understood. Finally, in the context of an election process and the triggers of election-related violence, the question as to how trust in institutions, the EMB and the election process itself can be eroded or bolstered bears relevance.

The study will explore the following questions:

It is beyond the scope of this exercise to provide definitive answers. Rather, it aims to explore the questions to inform future programming. The report shall consider the existing research and marry this with insights from election practitioners across the world.

Ultimately, this report posits that strong information integrity is vital to ensuring credible and peaceful elections. Its exploration of the subject is towards an understanding of what the risks are, how an information integrity environment may be achieved, and how this varies specific to the context.

Research has raised doubts about the ability of information pollution to convert voters to political positions that are markedly different than their own. However, there is clearer consensus that online information pollution can contribute to polarization within electorates and populations, thus raising the prospect of election-related violence (Barrett, Hendrix, & Sims, 2021). Specifically, literature is concerned with affective polarization and the tendency for partisans to dislike and distrust out-groups.

It has been found that exposure to false information deepens partisan beliefs (Guess A. M., 2020), with disinformation campaigns that adhere to a widespread belief or hold some basis as reality being particularly successful (Moore, 2018). Conversely, it has been found that simply by being off social media, individual polarization can decrease (Allcott, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, & Gentzkow, 2020). Overall, it is clear information pollution can be a polarizing force in the minds of voters and that its potential impact may be tied to the pre-existing levels of polarization in the country. How Global South countries present has not been well researched; however, certain metrics may support assessments of susceptibility to information pollution, such as polarization indexes, media independence and trust in institutions.

A popular explanation for online polarization is ‘filter bubbles’ caused by platform algorithms (Pariser, 2011) that are described as creating and amplifying echo chambers where people hear only similar views, which in turn validate opinions and drive polarization. Recent evidence challenges the strength of this theory (Guess, Lyhan, Lyons, & Reifler, 2018). This refined position holds that, while accepting that the ‘echo chamber’ theory is true for a few who conduct selective exposure, on average, users of social media are expected to experience more diversity than non-users (Newman, 2017). Thus, rather than being forced into echo chambers, this position views people who experience such as a self-selecting small minority of highly partisan individuals. Research on a handful of established Western democracies found only around 5 percent of Internet users exist in echo chambers, with the exception of the United States where rates of 10 percent or more exist (Fletcher, Robertson, & Neilsen). A reasonable concern is countries with high polarization will present akin, or worse, than the United States. Furthermore, communities with smaller linguistic pools may also present differently.

The outcome of personalization and recommender algorithms does not always lend itself to the echo chamber concern. One study conducted in the US demonstrated algorithmic personalization for people interested in false election narratives resulted in them being presented content more often challenging these false narratives (Bisbee, et al., 2022). Similarly surprising are findings that the forms of algorithmic selection offered by some search engines, social media and other digital platforms lead to slightly more diverse news exposure (Arguedas, Robertson, Fletcher, & Nielson, 2022). In particular, there is concern on what drives radical political content consumption on video-based platforms, with many pointing to the recommendation engine, while others contending it is a combination of user preferences, platform features and the supply-demand dynamics (Hosseinmardi, Ghasemian, Clauset, & Watts, 2021). However, what has been seen in the past may not hold, as more efficient algorithmic targeting develops, nor is there clarity on how these algorithms perform in different contexts.

Ironically, it has also been found that exposure to messaging by opposing political ideologies can entrench political views (Talamanca & Arfini, 2022) (Bail, et al., 2018). This implies that the greater diversity of political news exposure may exacerbate polarization, not diminish it. This may be reflected in findings that social media posts that reflect animosity towards opposing political views are significantly more likely to attract engagement (Rathje, Van Bavel, & Linden, 2021), which may incentivize such language and enhance the virality of such polarizing posts.

Ultimately the overriding concern is that the online space gives falsehood the advantage over the truth. One often-cited study used Twitter data to infer that information pollution diffuses “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly” than non-polluted information, especially prevalent in polluted political information, and that it was humans, not bots, that were responsible for this spread (Vosoughi, Roy, & Arel, 2018). While the extent of this research is contested on the basis of more recent analysis (Juul & Ugander, 2021), as newer platforms with more successful engagement techniques arrive, these trends may deepen.

Another cited phenomena of political engagement on social media is the incivility of online discourse, which it turn drives mistrust on- and offline. This falls significantly more upon women, reporting greater experience of these risks than men (Microsoft, 2022). In the political context, the highly evidenced harassment of female political figures online is of particular concern, imposing a barrier to their participation in the electoral process. Such acts are not only harmful in themselves, but also have negative consequences upon the broader electoral process. This influences the broader participation of voters and would-be candidates who find this unappealing, given that exposure to opposing views may reinforce existing views, and that discontent increases partisan acceptance of misinformation (Weeks, 2015), contributing to polarization.

In some ways, irrespective of the actual impact, the mere concerns by some that others may be influenced by disinformation has the potential to undermine confidence in democracy (Nesbit, Mortenson, & Li, 2021).

The degree to which people are exposed to information pollution may also influence its impact. In reality people typically consume little political news, with assessments finding that only a small amount of total online media consumption is spent on acquiring the news, and even a smaller fraction of this time is spent on fake news. For example, one study finds that for Americans, fake news comprises only 0.15 percent of the daily media diet, and news overall represents at most 14.2 percent of their daily media diet (Allen, Howland, Mobius, Rothschild, & Watts, 2020). In the months leading up to the 2016 US election, the average user is estimated to have seen between one and seven false stories online (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). Research into partisan WhatsApp groups in India found that little content was being shared that was hateful or misinformed (Chauchard & Garimella, 2022). However, not all people behave as the average, with a proportionately small group of people sharing a disproportionately large amount of extreme content (Mellon & Prosser, 2017).

In light of the limited exposure to online information pollution, consideration should be given to the powerful role traditional media outlets still hold in most demographics—particularly within the Global South. Assessments find that for many, it continues to outweigh social media as a source for news. While much attention is paid to the role of social media in spreading information pollution, it is only partially responsible for the spread, with traditional media also as a significant disseminator and shaper of the national information environment (Humprecht, 2018). This spread of information pollution by traditional media is in part driven by the newsworthiness of stories about false news and the need to repeat false news to address it (Boomgaarden, et al., 2020).

Irrespective of the actual impact, citizens often have a concern that others within their society are being unduly influenced by disinformation, and this belief alone has the potential to undermine confidence in democracy (Nesbit, Mortenson, & Li, 2021).

Election-related violence is typically a strategic decision to aid electoral success. Broadly speaking, the opportunities to manipulate the information landscape revolve around polarizing election competition along pre-existing social cleavages. Considering that ‘systemic, longstanding and unresolved grievances’ are among the factors that lead a country to be particularly susceptible to election-related violence (United Nations Department of Political Affairs, 2016), it follows that information pollution can be used as a device to help steer voters towards election-related violence through an avenue of political polarization.

Furthermore, there are findings that the electoral process itself does tend toward intensifying underlying tensions into high intensity situations where the quality of disinformation and propaganda becomes immediately inflammatory, increasing the likelihood that long-term discrimination will turn into physical violence (Banaj & Bhat, 2018).

More broadly, there has been work to understand how speech can be a driver of inter-group violence, including within an electoral context. While some researchers have posited a causal relationship, there is limited evidence, in part due to it requiring time to influence subjects and the difficulty of controlling for other influences (Buerger, 2021). While much study has been conducted looking at the role of television, radio or SMS, rather than the Internet, the findings suggest a relationship between the use of these channels to air messages that incite (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2011) (Deane & Ismail, 2008) or harmful rumors (Osborn, 2008) and the occurrence of election violence. Debate exists; however some research finds that the removal of hate speech online has benefits to offline violence (Durán, Müller, & Schwarz, 2022).

The threshold for mobilizing people to commit election violence is typically high. While some of the research raised above posits limited potency for using information pollution to influence the broad population, its ability to deepen polarization in certain segments of society can help to increase the propensity for election-related violence. Even the mobilization of relatively small groups of adherents is sufficient to instigate an outsized disruption of the election process.

Partisan violence lends itself to increasing approval by supporters, while driving away non-supporters, further exacerbating partisan polarization (Daxecker & Prasad, Voting for Violence: Examining Support for Partisan Violence in India, 2022).

The effects of information pollution vary between different demographics and contexts. Ultimately, for an accurate understanding of the influencing factors in a specific country, a case-specific landscape assessment is probably required.

History, society, culture and politics all play a part in understanding disinformation in a particular context, with an analysis of how social differentiation, such as race, gender and class, shape dynamics of disinformation. Institutional power and economic, social, cultural and technological structures further shape disinformation dynamics (Kuo & Marwick, 2021).

Since digital communication practices both exist within a particular socio-political context and shape that socio-political context, the relationship of violence is situated between the technological and social. Where the broader environment contains animosity towards particular out-groups, in-group users are predisposed to believe and share information pollution about out-groups (Banaj & Bhat, 2018).

Some countries appear more resilient to online disinformation than others. There are a variety of indicators that signal this resilience. These may include: the level of existing polarization, the types of political communication, trust in the news media, the presence of public service media outlets, fragmentation of audiences, the size of the advertising market and the level of social media usage. In practice, it is assumed that these criteria are more varied and context specific and will require an assessment to uncover.

Age has been demonstrated to be a significant factor in the sharing or acceptance of information pollution, as has political orientation. With age, older adults present this behaviour despite their awareness of misinformation and cynicism about news (Munyaka, Hargittai, & Redmiles, 2022). Gender, education and other identity features are considered to be less relevant, at least in some contexts (Rampersad & Althiyabi, 2019).

The underlying nature of relationships in a community may also influence behaviour, with trust in content and onward sharing potentially guided by ideological, family and communal ties. Behaviour is further influenced, for example, by the propensity to share and believe content guided by trust in the source (Banaj & Bhat, 2018).

Public trust in the conduct of elections is the cornerstone to the peaceful acceptance of the outcome, and a key guardian of this trust is the EMB (Elklit & Reynolds, 2002). The confidence held by election stakeholders in the EMB as an effective and impartial entity can underpin much of the resilience a process has to mitigate against the emergence of disputes and election violence. Many of the well-trod principles of effective electoral management continue to be relevant, such as impartiality in action, professionalism and, perhaps most applicable here, transparency (Wall, 2006) (Kerr & Lührmann, 2017).

Building the effectiveness of the EMBs as credible and capable institutions has long been a core tenant of electoral assistance and the prevention of election-related violence. However, the impact of new tools to undermine the integrity of electoral processes raises questions about the challenges EMBs may face in the future and how they should best respond. Similarly, there are clearly limits to what an EMB can achieve in an area that is outside of its traditional remit and which often has roots extending beyond the election process.

The formal responsibilities for the EMB will also depend upon their legal remit. Tasks such as monitoring the campaign and enforcing rules around advertising content and spending are complicated by the online realm. However, in order to defend the credibility of the institution and election, commissions may choose to proactively take action to improve the quality of the information environment.

There are increasingly troubling reports of election administrators being the targets of information pollution and harassment in the online and physical space (The Bridging Divides Initiative, 2022). There are concerns that increasingly public personal information and online data privacy issues provide more opportunities for attacks against public officials and techniques such as doxing (Zakrzewski, Election workers brace for a torrent of threats: ‘I KNOW WHERE YOU SLEEP’, 2022)(Zakrzewski, 2022).

Operating in the online domain, however, introduces a number of operational and financial challenges that are hard to overcome. Professional firms who work on social media analysis and attributing influence operations can be eye-wateringly expensive. The tools that exist are relatively immature and require a set of technical and analytical capabilities, which EMBs are not well-versed in. The platforms themselves often impose barriers to what State authorities can access by way of information. Taken together, the aforementioned obstacles call for investments in various capabilities and new approaches by international assistance providers.

While information pollution concerns are often viewed through the platform or citizen lens, some argue that this is inadequate, especially outside of Western contexts (Abhishek, 2021). For election-related information integrity concerns, a supply-side approach in which political actors are the key producers is a valuable prism to examine the impact of information pollution (Daxecker & Prasad, Poisoning Your Own Well – Misinformation and Voter Polarization in India, 2022).

Political entities and election-related violence

There is a wealth of analysis suggesting that political actors play a central role in the incitement of election-related violence. Incidents are typically conducted between parties, with incumbents the main perpetrators (Ginty & John, 2022).

Ultimately, for incumbent governments, the decision to foment election-related violence is driven by the fear of losing authority (Hafner-Burton, Hyde, & Jablonski, 2013). The act has varying purposes. In the pre-election period, it can be used to change the electoral competition in their favour, for example by depressing turnout or mobilizing supporters. In the post-election phase, it may be used against public demonstrations or to punish winners (Bekoe & Burchard, 2017).

Some scholars argue electoral violence should not only be viewed as a strategy wielded by incumbents or the opposition: individual motivations may differ from the political groups’ and leadership’s goals, leading electoral violence to be fuelled by individual revenge dynamics and grievances or local power competitions (Hafner-Burton, Hyde, & Jablonski, 2014). Additionally, countries experiencing armed conflict often see armed groups as perpetrators of electoral violence to achieve their own objectives, intertwining it with other forms of political violence (Daxecker & Jung, 2018).

Political entities and information pollution

Election periods are typically rife with political information pollution, often conducted or inspired by the political contestants—in particular opposition groups or embattled incumbents. The influence a political entity has over their supporters translates to their ability to convince them of the supposed veracity of information pollution narratives (Siddiqui, 2018).

The instrumentalization of information has always been part of electoral campaigns, being used strategically to further prospects—with potential advantage (Kurvers, et al., 2021). However, researchers believe political parties and governments are escalating their capacity to use social media for information pollution. Numerous cases have been identified where they are outsourcing activities to the private sector. Bots or enlisted influencers are being used to bolster efforts. There are various election-specific examples of candidates or parties using social media to voice their disinformation or instances of fake accounts to artificially amplify their messages. (Bradshaw, Bailey, & Howard, 2020)

The use of social media manipulation strategies has increased during presidential elections in many countries. This is propelled by the contracting of global data mining players to collect and analyse data on voters and electoral patterns and then use it to target advertising and messaging to influence decisions. Targeted disinformation campaigns in many countries have also aimed to sway the electoral outcome, undermining credibility and confidence in electoral institutions, and fueling social tensions and violence during elections (Mutahi, 2022).

A particular challenge represents the fact that many of the actors at risk of inciting election-related violence are often responsible for setting the rules around the electoral process, campaign and, to some extent, information pollution. Thus, any regulatory process should be inclusive and transparent to relieve concerns of conflicts of interest, grounded in human rights protections. Related, legislative approaches should look to bolster confidence by insulating regulators from political interference, as well as providing effective routes for appeals and redress (Report of the Secretary-General, 2022).

Challenges in moderating political entities

There is a difficult balance to be struck when considering the appropriateness of certain rhetoric by political actors around the election. While there is an understandable desire for politicians to be limited to sharing factual information, in practice this is a complex criteria to enforce. Furthermore, freedom of expression and human rights protections to impart information and ideas are not limited to ‘correct’ statements, as the right also protects information and ideas that may shock, offend and disturb. Prohibitions on disinformation may therefore border violation of international human rights standards, while, at the same time, this does not justify the dissemination of knowingly or recklessly false statements by official or State actors (UN, OSCE, OAS, & ACHPR, 2017). Broadly, there is an expectation that rights that exist ‘in real life’, should persist online.

Certainly, a different standard should apply to speech that infringes upon human rights or qualifies as hate speech or incitement to violence. Experience indicates that voter propensity towards election violence is low, requiring political elites to invest significantly to mobilize supporters to engage in violence. Among the most effective types of messages that can lead to election-related violence are those which stoke fear in their supporters, often targeting minority groups. The intersection between election-related violence and hate speech is particularly concerning (Siddiqui, 2018).

Key platforms specifically limit content moderation of materials posted by politicians. Given that in most cases election-related violence is incited by politicians, this weakens another line of defence—though perhaps justifiably so. Any restriction on political discourse should respect that election processes require freedom of expression and a plurality of voices. The decisions about which messages constitute harm can become complex in a process that is, at its heart, a contest between political rivals and ideologies seeking to win the support of the population. Unlike in other contexts, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are rarely authoritative official institutions to set out the relevant facts.

The mass media plays a vital role in shaping the degree of trust enjoyed by an electoral process. However, media institutions are currently experiencing a decline in their own public trust, with few countries reporting more than 50 percent of people trusting most of the news most of the time. Furthermore, increasing proportions of news consumers say that they actively avoid the news. How citizens consume news varies from country to country, though online news outlets are increasingly overtaking traditional media. Younger users are migrating from websites to get their news from apps. (Newman, Fletcher, Robertson, Eddy, & Nielsen, 2022). Research indicates the expected correlation between exposure to ‘fake news’ and lower trust in media institutions. It also reveals that greater exposure to information pollution may lead to greater trust in political institutions depending upon voter alignment with political entities in power and the specific media environment (Ognyanova, 2020).

The decline in trust in media has various causes, including the perception that media hold political or elite biases or that media outlets are subject to interference by politicians and businessmen. There is an overarching need for independent, transparent and open press reporting on electoral processes to permit better scrutiny and accountability of elections and their results. Accordingly, it is prudent to consider the media environment in the country to understand the tools at hand.

Independent public service broadcasters remain well trusted in those countries where they have been appropriately established. It has been contended that the structure of public broadcasting, as opposed to commercial broadcasting, poses some limits on its ability to counter disinformation but also provides protections from attacks, for example fiscal and structural resilience (Bennett & Livingston, 2020).

Journalists operate in a difficult and dangerous space. There are various reports of them being the target of harassment and even election-related violence, just as the practice of journalism is being degraded. However, the role of independent journalism has possibly never been more vital to the conduct of an election, as a means for providing scrutiny, transparency and public education (America, 2021).

Not all mainstream media adhere to journalistic standards. While media are rarely the instigators of violence, they can produce a political environment that is conducive for polarization and violence. In the context of armed conflicts, media frequently become polarized, acting as propagandists for conflict actors (Hoglund, 2008). Accordingly, it is prudent to consider the media environment in the country to understand the tools at hand and the need for media reform.

While foreign intervention in elections has taken various forms over the past decades, the evolution of the information environment has created unprecedented vectors for them to seek influence. There is broad agreement that such intrusions should not be tolerated. However, indications are that condemnation and impacts fall along partisan lines, with those who stand to lose from the action becoming more outraged and losing faith in the democratic process (Tomz & Weeks, 2020). However, here also there is debate over the level of influence that these actors can meaningfully wield, at least independent of domestic political cooperation.

There are scenarios where the foreign influence is channelled through State broadcasters, in which case the attribution is relatively simple, and mechanisms to better inform the public of the risk have some promise (Nassetta & Gross, 2020). Various actors have been working to better support the identification of such operations and to devise response strategies.

Threat actors have various means of deploying their information pollution. Of course, political entities typically have sufficient standing within their communities to personally instigate harmful messages—and in some cases it is part of their political platform—which their supporters will organically disseminate. However, in other cases they will enlist others to initiate and or amplify content.

The presence of bots has been a concern, with the power to amplify opinions—including information pollution—by increasing engagement of posts, as seen in past elections (Bradshaw & Howard, Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation, 2017) ( (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017), which has been seen to influence the agenda of media outlets (Vargo, Guo, & Amazeen, 2018).

Alternatively, humans can be engaged to disseminate and amplify partisan messages and information pollution narratives in a coordinated fashion, be it through the engagement of ‘influencers’ or the use of networks of humans (troll farms) directing account activity. A trend has been observed where the use of bots is giving way to human agents aided by technology (Bradshaw, Bailey, & Howard, 2020).

As discussed before, private strategic communications firms, enlisted to spread propaganda on behalf of candidates and political parties, are growing and deploying many of the tools described above.

Platforms are both the conduit for spreading online information pollution, as well as a potential actor in remedying such. A confluence of factors has led to finger-pointing at platforms for, at best, not being sufficiently motivated to manage harms, and at worst, putting profit over the well-being of their users (Haugen, 2021). Some contend that in order to boost engagement, personalization algorithms are designed to promote controversial content, regardless of the veracity, and the platforms are not motivated to appropriately moderate disinformation. Platforms themselves have on occasion contested this narrative, with some arguing that they delivered personalization without promoting sensational content since a shortsighted quest for ‘clicks’ would undermine their longer-term profitability and reputation (Clegg, 2021).

Platforms vary in their capability to address disinformation (Allcott, Gentzkow, & Yu, Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media, 2019) each with different policies, resourcing and technical features. While some platforms are more associated with information pollution than others, this may simply be a function of greater market share and relatively more transparency in their operations.

While most of the well-known platforms have signed up, at least, nominally, to the goals of protecting human rights and imposing a responsible content moderation policy, other platforms are emerging that do not share similar concerns, and research into them is yet to develop, for example, Rumble or Truth Social.

Content moderation and safety tools

Platforms are defined, in part, by their content moderation approach, as well as their features, design, commercialization decisions and algorithms. Content moderation policies and decisions help shape the culture and experience of the platform and compliance with the law, underpinning their safety and attractiveness to users. Despite this, platforms are frequently cited as being opaque about their content moderation policies.

Correctly moderating content is challenging, especially with the massive scale and velocity of information around an election overwhelming human moderation capacity. Unfortunately, while platforms have long applied artificial intelligence to conduct content moderation, there are serious limitations to such approaches, such as: inaccurate decisions, bias towards particular populations and potentially censoring political ideas (Gorwa, Binns, & Katzenbach, 2020). Ultimately, content moderation is unlikely to remove all offending material while maintaining all appropriate content. Instead success may be more realistically defined by the degree to which it is correct (Douek, Governing Online Speech: From ‘Posts-As-Trumps’ to Proportionality and Probability, 2021).

The effectiveness of content moderation will differ by medium of content, complicated by the move from text to audio and video. Encryption and ephemeral content pose serious hurdles. While particular content moderation measures exist to challenge end-to-end encryption, they are reserved for certain illegal content, such as child sexual abuse material or violent extremist materials.

There are concerns about how platforms vary their service and site safety features between countries. Companies will prioritize their attention and resources providing some countries a better class of service than others (Zakrzewski, De Vynck, Masih, & Mahtani, 2021). For example, Facebook only opens Elections Operations Centers to address information integrity in some countries (Elliott, 2021).

A common difficulty platforms face is moderating content in various languages, with their local contexts, nuances and dialects. Automated measures have limits, while human moderation is also challenging, especially for less used languages (Facebook Oversight Board, 2021) (Stecklow, 2018) (Fatafta, 2021). For many, this demonstrates an underinvestment of resources by platforms and the limitations of artificial intelligence.

Policies and legislation

Platforms and other electoral information businesses should remain committed to ensuring that their actions respect human rights (Human Rights Council, 2011). While the platforms have increasingly agreed to apply international human rights law to their content moderation policies, it may be insufficient in tackling the thorniest questions (Douek, The Limits of International Law in Content Moderation, 2021). For example, there are questions regarding whether international human rights law provides any basis for censure of information pollution systematically conducted by foreign parties (Ohlin, 2021). Also, its restrictions around coordinated behaviour—foreign or domestic—also are considered absent. At the same time, the attempts to align with international human rights law can shield platforms, to some degree at least, against States who attempt to impose repressive content policy.

Despite typically having special policy frameworks for electoral content, platforms face dilemmas as they seek to achieve censure of unacceptable behaviour, support to credible elections and protection of freedom of expression. Platforms and election practitioners are unlikely to always agree on where this balance sits and the actions taken.

Governments are increasingly pursuing forms of platform regulation. These include requirements to prevent or remove otherwise illegal content, including hate speech. Some regulation imposes a vaguer criterion covering legal but still harmful content. By and large, platforms already restrict some legal yet undesirable content, arguably to create a hospitable online environment, support monetization and adhere to the spirit of the company. However, there is the inevitable tension between the self-regulation a corporation seeks to apply and what is culturally and legally acceptable in a sovereign country. It is unsurprising that governments have sought to assert greater control over the social media platforms; there are concerns over how these controls may be instrumentalized by illiberal or authoritarian governments.

Much of the legislation planned or in-place contains massive potential penalties for non-compliance. Some fear a chilling effect as platforms steer towards over-censorship to be sure to remain within the law.

Policy makers and legislators have various ways to approach the regulation of content moderation. Some approaches focus on the handling of individual content decisions and determining what is ineligible. Content-specific regulation faces the various challenges described above, including the overwhelming volume of content to parse, the complexity of designing moderation rules and the challenge of making consistent and correct content moderation decisions. Regulating for more process around moderation has been increasingly welcomed, for example, granting people the right to appeal content moderation decisions and notifications of actions taken to their content. However, a new line of thinking considers how to regulate activity to address the broader systems in play and direct effort upstream of individual cases, for example, producing annual content moderation plans and compliance reports or separating internal functions to limit problematic incentives (Douek, 2022).

Election campaign advertising has shifted substantially from traditional to digital channels over the last decade, raising concerns about transparency and the effectiveness of campaign financing regulations. In some ways, political advertising becomes simultaneously more individualized, tailored and opaque. The approach increased the potential for polluted information being diffused among voters on a large scale, without oversight or interventions against politicians’ claims (Council of Europe, 2017). However, while some platforms seek to enhance transparency by publicizing archives of ads, the degree of access and detail in these vary substantially. Simultaneously, where some major platforms have banned political advertising, this may prompt a shift to alternative platforms with less regulation and transparency (Brennen & Perault, 2021).

Influence operations in pre-Internet traditional media can build support for political parties and lead to increased political violence in conflict environments or where there is civil unrest (Bateman, Hickok, Courhesne, Thange, & Shapiro, 2022). If the information ecosystem is to support healthy elections, all elements of media—traditional and online—must be considered and addressed. Just as the degree to which social media is a concern varies within and between countries, the broader media environment carries the same concerns.

Building and sustaining a strong information environment requires intensive and tailored effort. There are a range of options that can be applied, a list that will continue to grow given the pace of innovation and evolving landscape.

Judging which options are most effective is difficult. The empirical knowledge base on the efficacy of combatting influence operations is limited, except for fact-checking efforts—especially those efforts made by platforms themselves (Courchesne, 2021). However, we have attempted to compare the existing research with the experiences shared with practitioners to identify promising options.

As a guiding principle in the design of any plan, activities should avoid undue or onerous freedom of expression restrictions; rather, it should favour those creating an enabling environment for freedom of expression (United Nations, 2019) (United Nations, 2019)

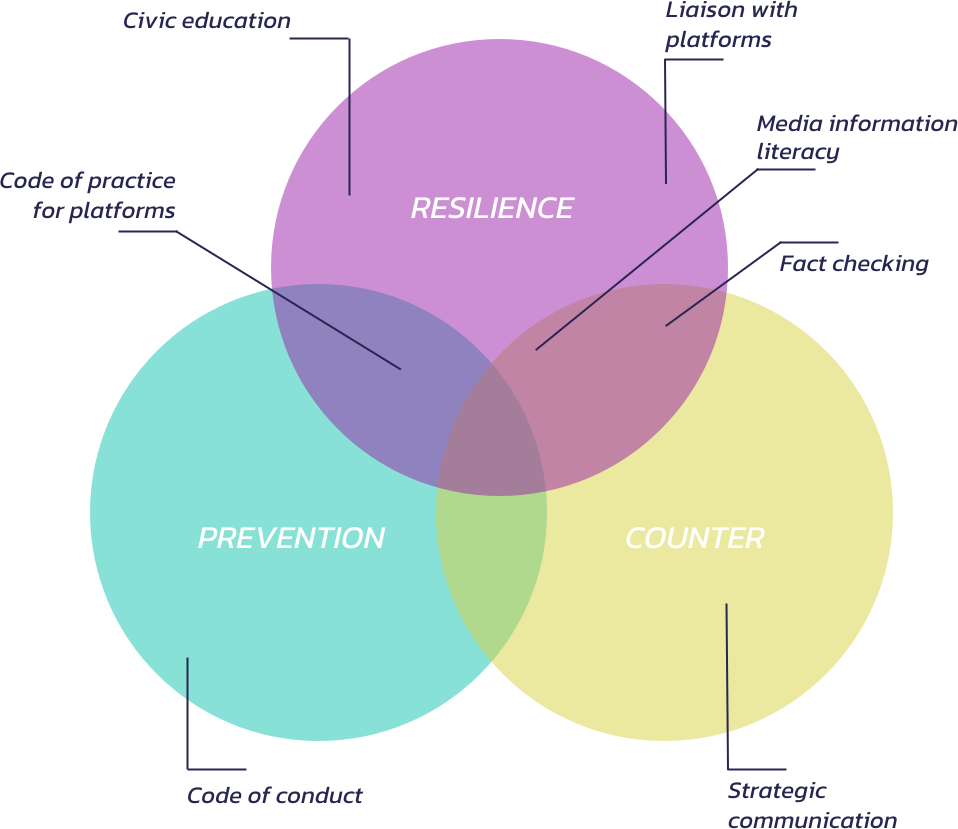

A healthy strategy should include a variety of responses attempting to address three broad categories of interventions. These categories provide a framework to support the design of a holistic set of activities.

Probably the most established pillar is to identify and attempt to counter information pollution. Fact-checking is the most established of such interventions, though others such as strategic communications and media monitoring are other variations of the same theme.

A commonly used technique to address beliefs from information pollution is to identify false narratives and communicate correct information. While ‘debunking’ or exposing a person to correct information may reduce misperceptions, it is limited in its ability to change people’s opinions on candidates (Nyhan, Porter, Reifler, & Woods, 2020)(Nyhan, Porter, Reifler, & Woods, 2020)In the face of corrections, the debunking effect is weakened when an audience supports the initial information pollution (Chan, Jones, Jamieson, & Albarracin, 2017).

Some posit a ‘backfire effect’ where corrections actually increase misperceptions (Nyhan & Reifler, When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions, 2010)though more recent findings contest these effects (Wood & Porter, 2019). Another related constraint is the so called ‘Streisand effect’, where the attempt to censor information leads to increased exposure of news compared to no action being taken (Jansen & Martin, 2015). The above highlights some of the limitations of fact-checking, identified by academic researchers and practitioners alike (Tompkins, 2020).

Broadly, fact-checking, however, has a positive impact (Walker, Cohen, Holbert, & Morag, 2020). How the debunking of fact-checking is communicated has a significant impact upon how effective it is. Of course, ensuring wide distribution is vital, as are the source of the information pollution and the speed of the correction (Walker & Tukachinsky, A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Continued Influence of Misinformation in the Face of Correction: How Powerful Is It, Why Does It Happen, and How to Stop It?, 2019). That is, if it provides the corrected details rather than just labeling and if it does not repeat the original falsehood. Where information pollution is being addressed, it is the trustworthiness of the source, rather than their expertise, which has the most impact on the permeance of the incorrect beliefs (Ecker & Luke, 2021).

Of course, these are not simple hurdles to overcome. In many cases, pulling together approved rebuttals can be a time-consuming process especially for complex and technical issues or where there are various approvals. The original sources are often not motivated to issue corrections, and universally trustworthy channels may be rare.

IFCN accreditation is a critical milestone for fact-checking institutions. While hard to achieve, it opens up a number of opportunities, including funding from platforms and access to data. However, it is also the case that a report by a fact-checking organization will not necessarily lead to action by platforms.

For fact-checkers, and those working with them, there are also protection concerns that should be considered within the establishment of a programme. Various fact-checking organizations across the world report operating in fear of government reprisals or public harassment. In some cases, the threats come with the association that fact-checking parties have with social media firms (Stencel, 2020).

Media and information literacy has been raised by many as the new silver bullet, a status once held by fact-checking. However, here also, practitioners should remain circumspect to the impact that can have. Clearly, a more critical and digitally sophisticated populace would naturally be expected to be better able to spot and filter information pollution. But there is already widespread concern among citizens in much of the Americas, Africa, the Middle East and Europe, with many countries demonstrating that over half their Internet users are concerned about false information online (Knuutila, 2022). That said, fear of information pollution is not the same as being resistant to it. There appears to be limits to the efficacy of digital literacy in preventing people from sharing fake information, even if it does increase their ability to identify such items (Sirlin, 2021). The design of such programmes also appears critical, as with one country-level example of election-related in-person media literacy. The study found their intervention had only limited ability for participants to identify information pollution, while motivated reasoning led to supporters of the incumbent becoming less able to identify pro-attitudinal content (Badrinathan, 2021).

It is also worth considering the pace of digital change in this context. While education for school-aged children is valuable in addressing various digital harms, it may be limited in the election content for no other reason than by the time school-aged children largely age to the point that they are politically engaged, some of the lessons may simply be redundant. While of course life-long education would also be valuable, it is not possible to implement as widely.

Another approach for fostering citizen resilience is to design peace and anti-violence messaging campaigns. Traditional versions of these have been demonstrated to have an impact in preventing electoral violence (Collier & Vicente, 2014) (UNESCO, 2020). Various actors are exploring how these campaigns can be effectively deployed online.

Social media has been instrumental in preventing, reducing and responding to electoral conflict and violence. For example, different actors have used social media to monitor tensions and violence as part of early-warning and response mechanisms. While social media can be a vector for inciting violence, it can also be used as a channel for spreading peaceful messages. It has provided a platform for political discussions, ushered in online activism and supported organizing and mobilization around political questions and demands. It has been used by various election stakeholders, including EMBs, the judiciary, security agencies, traditional media, civil society and political parties, to share information, dispel misinformation, fact-check, spread peace messages, conduct civic education and promote the participation of young people in elections (Mutahi, 2022).

A more targeted approach to building public resilience to information pollution is ‘pre-bunking’ or ‘inoculation’. Here, users are pre-warned of possible false narratives in an effort to limit their influence if encountered during the process (Cook, Lewandowsky, & Ecker, 2017), which has seen encouraging research. Different routes can be used to deliver such, including social media posts, video or even games (Roozenbeek, Van Der Linden, & Nygren).

Within an election, there are generally some obvious narratives that deserve pre-emptive action. To identify these, the first call would be to look at the electoral cycle to identify risk points, for example, the correctness of the voter register, the accuracy of the election results and disincentives to voting, among others. At the same time, it is not possible to identify or address all the narratives—and they will inevitably be unique from country to country—so triaging of the most damaging and likely threats is required.

Some of the same concerns and tactics that exist with debunking messaging remain valid, for example, taking care not to accidentally create or reinforce false narratives, structuring messages to be most effective and having strong coordination with media organizations (Garcia & Shane, 2021). Others hold concerns about the extent that inoculation is viable in ‘Global South’ countries since it does not address the specific political economy of propaganda specific to these contexts (Abhishek, 2021).

Member States are increasingly exploring legislation or binding regulations related to information integrity—specific to electoral events or with more general reach. The application of such approaches can be quite contentious, with possible concerns that they are unduly contravening freedom of expression, are imprecise or do not make a reasonable connection between the expression and a harm. Concerns exist that they might be misused by governments against critics and political adversaries (Khan, 2021).

The design of such policies should take into careful consideration human rights commitments, the broader democratic environment in the country and the nature of regulatory bodies and other institutions in place. The regulation should be carefully tailored and the result of a truly inclusive consultation, ultimately complying with the requirements of legality, necessity and proportionality under human rights law (Report of the Secretary-General, 2022).

Broadly, in many circumstances, it may be more appropriate to identify other mechanisms to curtail the actions of various actors, such as codes of practice or codes of conduct. At the same time, existing laws that censor defamation and harassment might suffice to tackle information pollution without the need for expansive new powers.

If the root of much election-related information pollution is political actors, then finding ways to dissuade them from engaging in such activities is logical, despite being challenging. Of course, they are not alone as creators or propagators of harmful content. Media entities, influencers and others are just some of the other potential sources.

Various methods may be used with these actors in order to attempt to dissuade them from engaging in information pollution. These may include, for example, codes of conduct, trainings, State monitoring and mediation. At the same time, programme designers should be realistic about the various competing incentives upon actors’ behaviour. Alongside these efforts may be monitoring activities to motivate compliance.

Electoral Management Bodies, political parties, candidates, citizens, journalists and other stakeholders have negotiated and agreed to a code of conduct during elections in many countries. While most of these cover general rules of behaviour by the actors, they have also incorporated social media elements. For instance, election stakeholders in Myanmar (2015, 2020), Georgia (2020) and Kosovo (2021) have committed to declarations/codes of conduct that regulate their social media behaviour ahead of elections.

Codes of conduct have proved particularly useful in enabling political actors to reaffirm their commitments to fair play in elections. Although investment in codes of conduct is promising, self-regulation may only have limited effects, especially if there are no robust enforcement mechanisms.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the codes of conduct is watered down if some of the individuals and groups who can meaningfully contribute to the code’s implementation and whose actions could exacerbate conflicts do not sign it. It has been particularly useful in some contexts for the monitoring committees of codes of conduct to have a presence on social media and communicate directly with the public about their monitoring. Furthermore, it is important to build local and individual buy-in for codes of conduct (Mutahi, 2022).

While each platform has its own features, user culture, monetization model and content rules, they each have significant levels of control over what content is published on them and how this is distributed. However, they demonstrate varying levels of investment in addressing information pollution, as well as, at best, mixed outcomes. Be it by working with platforms or conducting advocacy towards them, it is possible to make a meaningful impact upon the information ecosystem. In-country election practitioners are often well placed to identify risks that need to be navigated, communicate features that should be deployed and identify areas of collaboration.

One increasingly common tool of note is the establishment of codes of practice—which may be a more desirable approach to governing platform behaviour than legislation. Social media codes of conduct regulate discussions on such issues as disinformation affecting elections and trolling, which if left unchecked undermine the public’s trust of the electoral process and its legitimacy. These may cover the activities of platforms alone or also incorporate political parties. For the 2021 Dutch legislative elections, political parties and Internet platforms including Facebook, Google, Snapchat and TikTok agreed on voluntary rules in a code of conduct, the first of its kind in the European Union. The companies made transparency commitments regarding online political advertisements during election campaigns. Another country that has launched a social media code of conduct is Kosovo.

Media codes of conduct have come to now encompass social media as another way of regulating online speech during election periods. Technological innovation is also underway by third parties. For example, users may also be able to take actions to protect themselves, using the tools available; for example, services are being built to prevent online harassment, where platforms permit them (Chou, 2021).

The design of such policies should take into careful consideration human rights commitments, the broader democratic environment in the country and the nature of regulatory bodies and other institutions in place. The regulation should be carefully tailored and the result of a truly inclusive consultation, ultimately complying with the requirements of legality, necessity, and proportionality under human rights law (Report of the Secretary-General, 2022).

Broadly, in many circumstances, it may be more appropriate to identify other mechanisms to curtail the actions of various actors, such as codes of practice or codes of conduct. At the same time, existing laws that censor defamation and harassment might suffice to tackle information pollution without the need for expansive new powers.

If the root of election-related information pollution is political actors, then finding ways to dissuade them from engaging in such activities seems logical, whilst being aware of the challenges. Of course, they are not alone as creators or propagators of harmful content. Media entities, influencers and others are just some of the other potential sources.

Various methods may be used with these actors in order to attempt to dissuade them from engaging in information pollution. These may include, for example, codes of conduct, trainings, state monitoring and mediation. At the same time, there should be realism on the part of program designers with regards to the various competing incentives upon their behavior. Alongside these efforts may be monitoring activities to motivate compliance.

There is no reasonable way to control exactly what content exists on the Internet or even an individual platform, and even if there were, there is no consensus on what should be disallowed in the name of information pollution.

Some electoral information integrity challenges are ingrained within political culture, electoral processes and questions around how to apply fundamental human rights. International conventions provide some direction on the types of behaviour that should be addressed with censure, and voters certainly deserve reliable information, yet there are a host of grey areas. The intrinsic nature of electoral competition creates a complex set of dynamics whose harms cannot be fully neutralized, only ameliorated.

While the toolkit to protect the electoral information ecosystem continues to grow and mature, each activity or approach comes with its own limitations and trade-offs. At the same time, the challenges are evolving, thus eroding the capacity of previous approaches.

The absence of a silver bullet demands a multi-pronged approach. These should be designed to ensure complementarity between the various endeavours and that they are tailored to the specific local context. As discussed in more detail within separate recommendations, responses should look to consider means to build public resilience, attempt to limit the creation of information pollution and respond to information pollution. Furthermore, the approaches should be designed with consideration of the broader information integrity activities and concerns that exist outside of electoral periods.

Given the lack of evidence on what measures are particularly effective, it further makes sense to avoid putting all eggs in one basket. However, not all these activities can or should be delivered by one actor.

While the new information landscape and threats have created a range of novel and exciting programming options, the core task of successfully running an election that is credible remains vital. Support to the professional conduct of an election is made only more necessary by the new fragility of the information ecosystem. Established routes to build trust in the electoral process should underpin and overlap with work focused on the information ecosystem. Related to this is the heightened value of transparency. If information has become the core currency online, and if genuine and plausible information is not published, then there is an opportunity for another actor to fill the vacuum with false and harmful messages.

No single entity can resolve the myriad of information integrity challenges present in an election, and certainly not an EMB alone. The diverse range of organizations working on these issues is encouraging; however, how they work together is likely key to their collective success. Different models of partnerships are being developed. Election ‘war rooms’ provide for a joined-up crisis response. Social media councils are envisaged to allow coordination on advocacy. Information integrity coalitions bring together government and non-governmental actors including the private sector, political parties and ordinary citizens.

An effective programme of work requires a multi-stakeholder approach and the ability to creatively craft solutions. There are choices and actions that can be taken by the various actors in an election process, including citizens, civil society, State authorities, private sector platforms, traditional media and, perhaps most importantly, political figures. Together, they can build a strong information ecosystem to aid peaceful and credible elections. Multi-stakeholder dialogue and collaboration on social media and preventing electoral violence should therefore be promoted and involve national authorities, social media companies, political parties and civil society.

Each election is defined by a host of factors, creating a unique set of risks and opportunities. A starting point for any exercise should be an assessment of the information environment, directed by the particular political, security and social concerns in the country. Given the rapidly evolving dynamics, a continuous review should be in place as much as possible.

Cut broadly, interventions fall into two camps. The first is to address concerns by imposing controls over the information ecosystem. While potentially essential in some cases, such activities may be to the detriment of freedom of expression, the right to participate in public affairs and other essential human rights—intentionally or as an unfortunate side effect. Such efforts may ultimately undermine trust and threaten the credibility of the election.

Rather, interventions rooted in the protection and promotion of human rights should be prioritized, for example those which seek to promote transparency, access to information, media freedoms and public education. Where restrictions are to be established, they are expected to meet a high threshold of legality, legitimacy, necessity and proportionality.

A practical component of this, on the platform side, should be an adherence to human rights due diligence and regular transparent impact assessment. These may be guided by the approaches outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2011).

While elections are clearly a vital part of any democratic society, actions taken to secure them should also consider the broader democratic landscape, human rights environment, and how these relate to digital rights.

In practical terms, this calls for caution when providing advocacy or advice on legislative or regulatory activities. While there are certainly flaws with the approaches taken by platforms, risks—perceived or otherwise—should be balanced against an increase in State authority. While there may be legislative approaches that are adopted in some countries or regions, it is not necessarily wise to transplant them to another context. Certainly, given the novel nature of much legislation, little evidence has been collected on how they materially impact an election even in the contexts they were designed for.

Rightly, in most democracies, campaign regulations have long been in place to provide at least some semblance of a level playing field and to impose some guardrails on speech around the political process. How these translate onto the online space remains a work in progress, and one that is not solely in the control of the national authorities, with platforms often in the driver’s seat.

The research and conclusions drawn above point towards the threat that information pollution poses with regards to polarizing voters and politics, and how these can threaten credible and peaceful elections. We identify negative synergies between information pollution and incitement to election-related violence. They both rely on the existence of underlying cleavages, which they can inflame and exploit. Hence, practitioners should prioritize activities that aim to ease societal tensions, address excesses of division and foster confidence in the election process.

While there are various threat actors, by far the most potent in an election context are domestic political actors. These dominate as the sources of information pollution, driven by a motivation to incite election-related violence or discredit an election.

However, the means to constrain political actors may be limited. Using regulatory tools or codes of conduct can have a positive influence, supporting the negotiation and implementation of codes of conduct on online campaigning and the use of social media by the different electoral stakeholders can contribute to diffuse tensions. Monitoring and sanction mechanisms can help motivate compliance.

Support to the appropriate actors involved in advocating or guiding social media regulation, as well as on advocacy and monitoring of codes of conduct and platform codes of practice, is important. Broader programming is also required to respond more effectively to alarming rhetoric in a timely and persuasive fashion, before it has the opportunity to deepen divisions and drive election-related violence.

For some time, fact-checking was the first and only line of defence against most forms of electoral information pollution. However, evidence and the experiences of many in the field indicate that its effectiveness is less definitive than hoped. It faces the challenge that it is hard to change people’s minds once they have formed ideas that correspond to pre-existing beliefs. While fact-checking is a vital tool for accountability, and indeed, has some value in mitigating against information pollution, it should instead be considered the last tool—with additional attention being paid to ‘up-stream’ resilience.

Much of the attention given to building public resilience to information pollution is warranted. Increasing the public’s ability to critically assess content and identify information pollution can help to nullify its impact. There are a variety of methods that are being considered here, for example: digital, media and information literacy, and pre-bunking.

However, its effectiveness should not be overstated. As explored before, the receptiveness to disinformation may be less related to the knowledge that it is false, than that the themes align with the recipient’s political bias. Thus, enhanced media literacy is valuable but cannot resolve some of the most dangerous scenarios.

This also carries a number of difficult operational challenges, such as the complexity of reaching broad audiences, difficulties to identify most at-risk individuals and the need to commence well in advance of an election process.

Building trusted and capable institutions represents one of the more traditional approaches to preventing election-related violence and remains vital. If anything, the more fluid the information landscape the more important it is that technical mistakes in the operation of the election are avoided, and that when they do take place, they are well communicated to the public.

Specifically in the case of information integrity threats, it is clear that the EMB cannot assume all burdens in combatting these threats. However, while the mandates of EMBs and other relevant State institutions will vary between countries, some programming aimed at promoting information integrity remains inescapable. At a minimum, they will be required to protect their own institutions from attacks or defamation if they are to support the credibility of the election, and to do so, they require the tools—and financial resources—to defend themselves.

The myriad of new challenges that election EMBs will need to address require a different technical toolkit, which in turn will generate additional requirements for providers of election assistance. Beyond the EMB, other domestic regulatory authorities, as well as civil society and the media, can also be supported to operate in this new domain, for example with advice on online monitoring of hateful messages, investigations, counter-messaging and conflict-sensitive coverage of the elections.

The integrity of the information technology infrastructure and data of institutions and public officials is also vital, in particular as they provide an intersection with information pollution. Election Management Bodies in particular hold significantly sensitive systems such as their voter register and results tabulation systems. Hacked data can be leaked as part of misinformation campaigns. Furthermore, there are cases of public officials being harassed and having their online information misused. Accordingly, the cybersecurity and cyber hygiene practiced can have a tangible impact upon exposure to information pollution—and this is another space in which support may be provided.

How and whether these activities and tools can be funded in a sustainable fashion remains a question. This is an even more acute concern when we remember the purveyors on information pollution are increasingly funnelling capital into their activities.

Journalism and the traditional media outlets have long been a vital component of a healthy information ecosystem. For various reasons, some related to the new digital platforms, the practice of journalism is under increasing attack and suffers diminished trust.

As with other electoral components, codes of conduct agreed between media outlets can be used, to some extent, to incentivize professional coverage and build public trust. In countries where there is concern of media capture by partisan interests, this likely requires strong monitoring to be effective.