The framing of this workstream is guided by the definition of election-related violence put forward by the United Nations Department of Political Affairs, as “a form of political violence, which is often designed to influence an electoral outcome and therefore the distribution of political power”. It may take the form of physical violence or other forms of aggression, including through coercion or intimidation. Incidents of violence can take place prior to and during polling, as its perpetrators may seek to influence electoral authorities, candidates, observers, journalists, or voters and therefore the results; or it may take place during or following counting, aggregation, or publication of results, when the intention may be to influence the future distribution of political power or negate the results. Since electoral processes are methods of managing and determining political competition with the outcomes deciding a multitude of critical issues, it can lead to a highly competitive environment where underlying societal tensions and grievances may be exacerbated, resulting in electoral violence.

Violence against women during elections prevent women from exercising and realizing their political rights in both public and private spaces. It is driven by gender-specific motivations and discrimination, notably as women contest and deviate from traditional gender roles and engage in political life. The most apparent motivation behind the violence is to prevent women from their independent political participation, exercising their electoral right or from pursuing a political career.

This workstream is further guided by the broad understanding of women’s political participation as a fundamental prerequisite for gender equality and inclusive governance. It facilitates women’s direct engagement in public decision-making and can be a mean of ensuring better accountability to women.

Although violence against women in elections has remained in the margins of study due to the lack of reporting and available data, as well as limited understanding about the issue in cases and general stigma attached to gender-based violence in many societies, there is a growing attention given to the topic in policy making and academia. This workstream does not intend to duplicate what has already been published, but rather to complement existing literature on the topics by providing concrete examples of programming that can enhance practitioners’ understandings of the issue, as well as identify innovative interventions for both the prevention of gender-based electoral violence and women’s meaningful political participation.

Young people often act for peace in their communities, hold political leaders to account for climate promises and deliver relief to the most vulnerable people, among other areas of action. However, there is low youth participation in formal politics in many societies. Young people and their organizations, movements and networks are more likely to engage through informal processes and alternate spaces. Formal participation can be understood as engagement in established processes or institutions, whereas informal participation refers to people’s organization for political, social or economic aims outside the realm of political parties and formal institutions. In order to understand youth leadership and agency during elections, it is important to consider these alternative forms of participation such as youth civic activism and social movements, and that non-participation is also a form of participation/political expression. The youth survey and consultations of this research process have been a testimony to this.

Young people are not a homogeneous group, and electoral-related programmes would benefit from considering how the various identities of young people intersect and the impact of this in specific contexts in order to promote the participation of young people in their diversity. Leaving no one behind is a principle for sustainable development. To leave no youth behind during the electoral process, stakeholder analyses should be sensitive to young people’s identities relating to class, caste, religious affiliation, tribe, ethnicity, gender, age, people with disabilities and rural/urban, among others.

This research report is among the deliverables of the gender equality and women’s participation workstream of the Sustaining Peace during Elections (SELECT) project and was developed to deliver on the content of the project output 1 for the development of an online knowledge hub and to be used through the project on output 2 for capacity building and outreach. The research process has been designed to be inclusive and participatory to ensure the content produced in the final product has a multi-regional lens and takes into consideration experiences and knowledge from a wide range of stakeholders, including civil society.

Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966) enshrines the rights of all citizens to “take part in the conduct of public affairs” and “to vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the electors.” While the ICCPR establishes that no discrimination on the basis of sex is permitted in the exercise of the rights to vote and to participate in public life, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, – adopted in 1979 and ratified by nearly all Member States – goes beyond this approach, placing a positive obligation on States parties to take all appropriate measures to end that discrimination. For example, Article 4 of the CEDAW encourages the use of Temporary Special Measures (TSMs) to accelerate the achievement of de facto equality, in light of Article 7 of the Convention.

Women’s right to participate fully in all facets of public life has continued to be a cornerstone of UN resolutions and declarations, including in the Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action (1995), the Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (2000) and the General Assembly Resolution 66/130 on Women and political participation (2011). Through them, governments have consistently been urged to implement measures to considerably increase the number of women in elective and appointive public offices and functions at all levels, with a view to achieving equal representation of women and men, through affirmative action, if necessary, in government and public administration positions.

In addition, Sustainable Development Goal 5, which focuses on achieving gender equality and empower all women and girls seeks to “ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life” (target 5.5.). Furthermore, Sustainable Development Goal 16 on promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, and providing access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”, cannot be achieved without ensuring equal opportunities for men and women to participate in politics and elections.

This normative framework lays the foundation upon which the international community can show its commitment to ensuring women’s full and meaningful political participation, and to actively work on preventative measures to respond to and eliminate gender-based violence targeting women during electoral processes.

The United Nations Policy Directive on Preventing and Mitigating Election-related Violence defines electoral violence as a a form of political violence that is often designed to include an electoral outcome and therefore the distribution of political power. It can manifest itself as direct physical violence or take on other forms of aggression, such as intimidation, harassment, or coercion.

Electoral violence can occur during any point of the electoral cycle; be it atthe point of voter registration, political campaigning, polling day or to the announcement of results. Critical to point out is that most understandings and definitions of electoral-related violence focuses on the public sphere, often overlooking violence happening in the private sphere where most forms of gender-based violence do occur.

Violence against women or gender-based violence in elections is a specific form of violence that may have severe effects on women’s political participation, sometimes hindering them from standing as candidates, discourage women from voting or even punish them for taking active parts in the electoral process and realizing their political and electoral rights, including the right to vote, hold public office, to associate or assemble. It can take the form of direct physical violence or be the threat of violence resulting in physical, psychological harm or suffering. Following this definition, violence against women during elections is, indeed, a form of political violence intended to impact the realization their electoral and political rights.O

A wide range of actors are working on measures to support women’s political participation across the electoral cycle and in electoral processes, including international organizations, Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs), civil society, media platform, think tanks and others. While there has been an increase in efforts amongst electoral practitioners with the objective to enhance gender equality in electoral assistance and programmes, less programmatic focus has been on the role that deeply ingrained social and cultural norms play in hindering women’s meaningful participation.

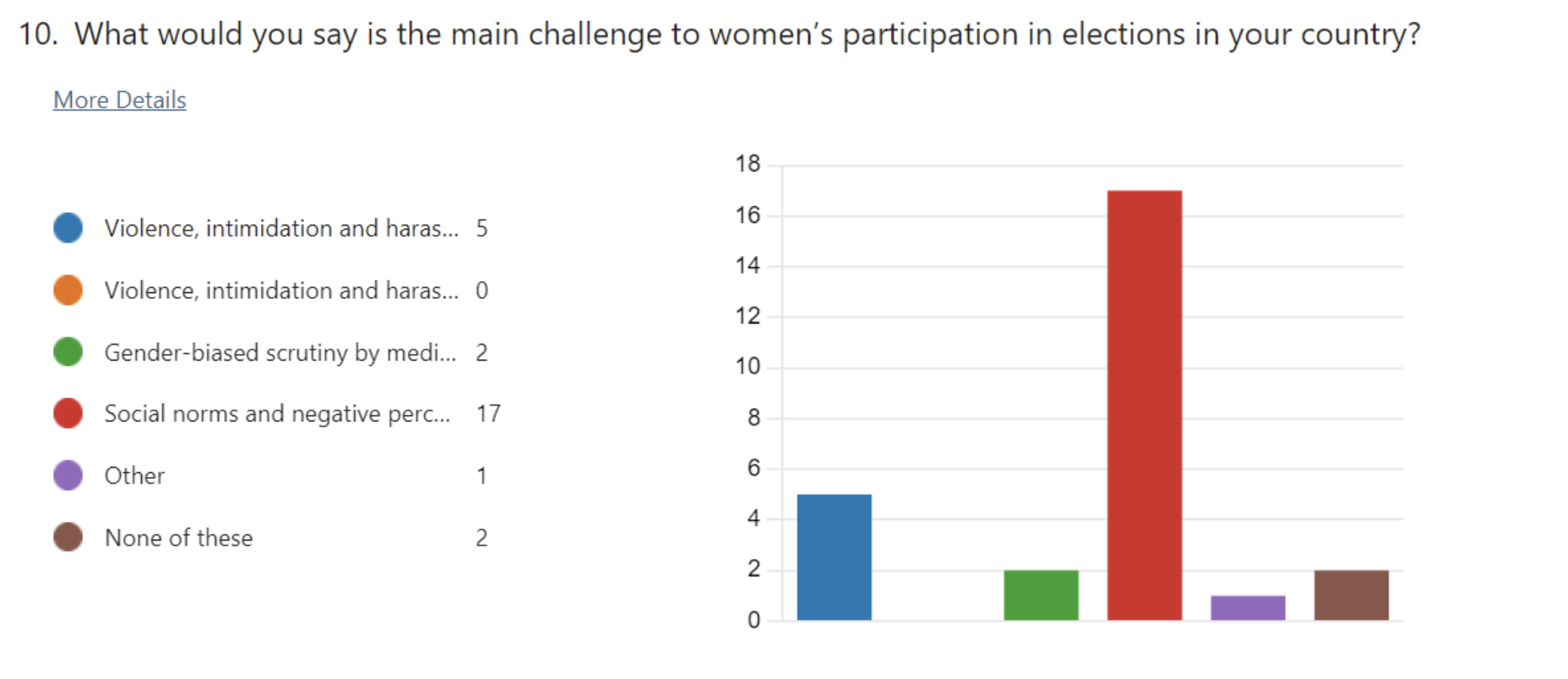

Such norms are often the very root causes of violence. We know today that deep-seated patriarchal belies can relegate women to less active roles in political processes, including elections, and can, at times, normalize violence against women, both as means to exerting control and as a tool to dissuade women from challenging traditional power structures. In electoral processes, where power dynamics are heightened, these negative norms can manifest in various forms of intimidation, harassment, and even physical violence aimed at deterring women from running office or participating actively in campaigns. As is becoming increasingly evident, addressing and challenging these entrenched norms is crucial for creating inclusive political environment that can ensure women their active, full and equal participation in decision making processes.

Notwithstanding its prevalence, violence against women in politics – and particular the topic of gender-based violence in electoral processes – has remained in the margins of study often due to lack of reporting and available data, but also because of stigma attached to it in many societies, which further amounts to a lack of understanding of the issue in contexts where it is less openly talked about. Traditionally, electoral violence has also been defined with less focus on women’s unique experiences, such as psychological abuse, harassment, or intimidation, amounting to critiques of such definitions being genderblind.

Oftentimes, gender-based violence violence takes on a subtler form, many times occurring in private or domestic spheres, they have not been part of the mainstream understandings of election-related violence. This has resulted in a lack of collected data to measure standard indicators in many electoral programmes to measure its prevalence or to document trends on a global scale. Datasets on national levels rarely incorporate or even recognize gender-specific forms of violence, which also, shows a lack of systematically collected data, keeping the topic incomplete.

The information gap is also due to underreporting by victims at times violence occurs. A so-called “culture of silence” is rather a trend than an exception in most cases. As pointed out by scholars and practitioners, this is has its origin in a “culture of impunity” associated with violence against women, for instance; women keep away from reporting different forms of violence, women candidates have reportedly concealed threats in order to avoid appearing “unfit” for a political appointment. Other reasons for the “culture of silence” can be lack of media coverage on the issue. Violence against women in elections remains underreported in many countries. In addition, women continue to be underrepresented in leading roles in media outlets and platforms, including as reporters, which means that its mostly men that set the agenda of the daily news production and of what constitutes as “newsworthy”.

Lastly, a lack of political will to prevent, address and mitigate occurrences of gender-based violence is often singled out as a key factor to its underreporting and continued prevalence. The UN Secretary-General Reporting “In-depth Study on All Forms of Violence against Women” (2006) framed it as a lack of political will “reflected in adequate resources devoted to tackling violence against women and a failure to create and maintain a political and social environment where violence against women is not tolerated”. With growing commitments from the international community to prevent and mitigate violence against women in elections there is growing agreement and hope that this, however, is slowly changing.

The issue of tackling violence against women during electoral processes is particularly pressing as women already face greater barriers to participation in public life and experience highly distinct forms of violence – specially forms that are often overlooked or hidden, including sexual assault, intimidation and threats. Ensuring perpetrators do no go unpunished is not just an issue of individual rights, but one of broader electoral justice and electoral integrity.

Despite women’s rights to equally engage in democratic processes and their undeniable abilities as leaders and agents of change, women’s political participation and their taking of leadership roles continue to be restricted from global to local levels across. For instance, recent data from the “Women in Politics: 2023: Map” shows that women serve as Heads of State and/or Government in only 31 countries across the world. Further, women make up 26.5 per cent of Members of Parliament, and globally less than one in four Cabinet Ministers is a woman (amounting to 22.8 percent).

Structural barriers such as discriminatory laws and institutions continue to pose obstacles to limit women’s option to run for office, and capacity gaps such as lack of education, keeps widen this gap even further. Yet, we know that that women’s political participation is paramount for the advancement of gender equality: when women are actively engaged in politics, their experiences and priorities are better represented in decision-making processes leading to more inclusive societies. Increased representation of women in leadership positions also help to break down stereotypes and barriers, empowering women take part in politics and foster a new culture that can pave the way for future generations.

Considering the above, the need to combat discriminatory legislation and policies to improve gender equality outcomes in policymaking by creating structures and strategic plans to enhance women’s political participation is becoming a growing focus area of various stakeholders in the electoral community, as well as among international actors and governments, international organizations, civil society, think tanks and others. That also includes the creation of systems that can help recognize women’s essential role in empowering women as parliamentary representatives, supporting the emergence of gender-sensitive parliaments, and adopting gender-sensitive policy and legislative frameworks.

Gains in women’s participation have indeed been notable in countries that have taken proactive steps to support such measures, including reforming or amending discriminatory laws, taking concrete action to address violence against women in politics and gender discrimination within parliaments, addressing gender-specific barriers, and supporting women in all forms of decision-making including at local level and in executive government.

Evidently, women’s political participation continues to face multifaceted challenges globally, varying significantly across different contexts. In many regions, discriminatory laws and institutional barriers persist, limiting women’s access to political positions and decision-making processes. Economic disparities can further exacerbate these challenges, particularly in contexts where women lack the resources and support networks necessary to pursue political careers. In addition, women from marginalized groups, such as indigenous communities or ethnic minorities, can face intersecting forms of discrimination that compound the different obstacles they may encounter.

Post-conflict societies may also present a set of obstacles to women’s equal participation in elections, such as volatile security situations, heightened gender-based violence, the exclusion of women from peace negotiations which further determined the type and details of the electoral system and process, lack of investment in bringing together women as political actors, and inadequate institutions for the protection and enforcement of women’s rights. At the same time, post-conflict contexts may also provide a unique opportunity to introduce a more inclusive political framework and advance women’s political participation, including through peace-building efforts as well and political processes.

Around 200 people in total were engaged in the research process, covering 40 countries, as well as individuals from regional organizations.

The foundation of the research project was formed by a series of workshops, consultations and discussions that were held with practitioners and experts in the fields of information integrity, conflict prevention and elections, as well as a survey that was distributed online. Some of the discussions centered around challenges in certain regions, while others were with experts on a specific thematic topic. Several themes were identified, some of which were common across the geographic regions engaged, while others differed depending upon the context or type of interlocutor.

The participants were predominantly from United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) working in the field of governance, peacebuilding and gender equality, but also from development partners including the representatives of the EU, civil society organizations, national electoral bodies from the global South and working on specific country contexts.

The two Working Groups met on a regular basis during the research process to discuss ongoing findings from the research process and share inputs from the regional consultations. Participants came from UNDP and other UN agencies, such as UN Women, the United Nations Department of Political Affairs, the EU, civil society organizations, such as IFES, intergovernmental organizations such as International IDEA, academia, think tanks and other independent experts on topics related to gender-based violence, women’s political participation and gender equality matters,

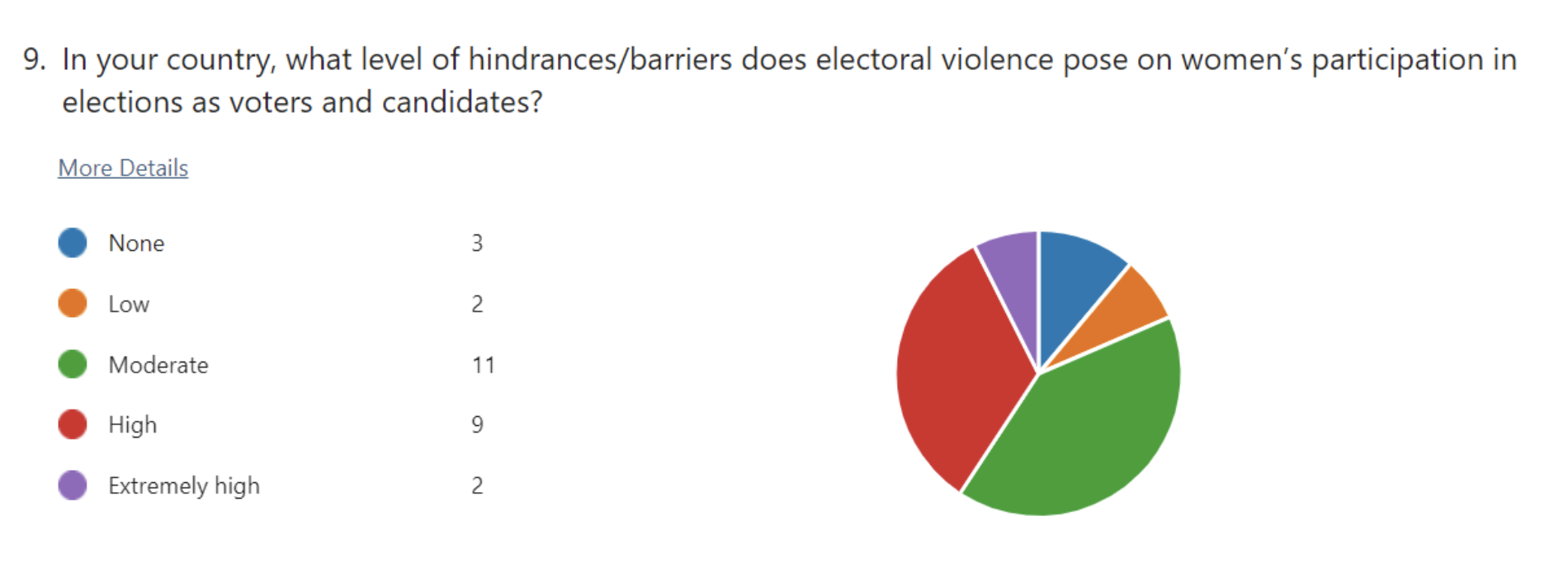

As part of the research process, a global survey was sent out to practitioners captures a growing need to work towards tackling root causes of violence, pointing towards addressing root causes of violence. The survey on gender equality in the context of elections was designed and sent out to practitioners at regional and country to provide insights on current programming, projects, and interventions. The survey was hosted online and circulated through networks of national electoral practitioners as well as development partners and stakeholders.

The analysis of open-ended questions applied qualitative content analysis to determine themes and draw findings from the textual responses.

A widely discussed topic was the need to involve a broad range of actors, both champions and those more cautious or placing question marks. For example, it was mentioned that involving so-called “gatekeepers” in communities, such as religious leaders, prominent elder leaders, can open up possibilities of involving a wider range of actors in such efforts.

Another suggested intervention was to conduct trainings in non-violent communication with men and boys, which can help foster dialogue and, eventually, challenge masculine ideals and behaviors that can lead to violence.

Barriers in sustained project funding and possibility to scale up projects related to women’s political participation remain. The importance of ensuring collaboration and partnership among UN agencies was also stressed.

A few words on limitations are important to add to this report, as it relates to the following subthemes.

Consultations: Some issues considered sensitive will rarely be discussed during multi-stakeholder meetings. Therefore, the research has relied upon other data and studies to provide insights into areas such as gender-based violence, threats towards women – and particularly young women – engaging in civic space, in particular in certain context where civic space is shrinking or currently under threat.

Survey: Designing global surveys is difficult for obvious reasons, attempting to pose generic questions to capture and address context specific issues. The survey was shared online, which also creates limitations; some respondents might not feel comfortable sharing certain levels of information and other target audience might not have or limited accelerating to the digital divide since the target group had access to the Internet. This has been considered when drawing conclusions from the findings of the youth survey, and a youth consultation was hosted to validate the findings. As the survey was shared online it proved difficult to get enough respondents.

Desk research: As with all desk research, it runs the inherent risk of not identifying best practices from the ground, particularly from hard-to-reach areas. Multiple conversations and dedicated consultations with practitioners with over 200 participants across all regions working predominantly at country levels in the field were, however, held to overcome this potential research gap.

Each election is defined by a host of factors, creating a unique set of risks and opportunities. A starting point for any exercise should be an assessment of the context; its environment, directed by the particular political, security and social concerns in the country.

Given the rapidly evolving dynamics, a continuous review should be in place as much as possible, with a specific focus on gendered dynamics. This is critical for all interventions and particularly needed when addressing gender-based violence since different activities may be a better fit in certain context, for example different reporting mechanisms or hotline systems. In other, it may be more appropriate to work to strengthen legal reform, especially if such a legal landscape is not yet well developed.

A growing and urgent need to work more targeted towards tackling root causes of violence and women’s exclusion in electoral processes, be it as campaigner, staff or voters, has been highlighted time and again. This particularly includes working preventatively on tackling negative social norms and perceptions against women’s involvement in political life. Conducting a social norms assessment can provide invaluable insights into underlying beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that shape political participation.

By understanding the prevailing social norms, including gender roles, power dynamics, and expectations surrounding electoral processes, stakeholders can identify specific barriers that hinder women’s participation and perpetuate inequalities. Such an assessment enables policymakers, civil society organizations, and electoral authorities to develop targeted interventions and strategies that challenge harmful norms and promote greater inclusivity and equality in electoral processes.

By engaging diverse stakeholders and communities, a social norms assessment can facilitate dialogue and consensus-building around gender-sensitive approaches in such processes.

This is essential for fostering inclusive electoral processes, as it addresses the root causes of gender inequality and promotes collection actions towards inclusion and gender equality. By engaging men and boys as allies in efforts to promote women’s political participation, it is possible to challenge traditional notions of masculinity and power dynamics that often exclude women from decision-making processes.

Through education, awareness-raising, and dialogue, men and boys can become advocates for gender-sensitive polities, activities and practices within their communities and institutions. In addition, involving men and boys in initiatives aimed at promoting women’s leadership can both help to cultivate empathy and understanding as well as it can break down resistance to change and foster a sense of shared responsibility for achieving gender equality in electoral processes.

It is shown time and again that introduction of TSMs are effective tools for supporting women’s participation in political processes and elections since they provide targeted interventions to address systematic barriers and inequalities. Different TSMs, such as quotas or reserved seats for women, can help create opportunities for women to access political positions that they otherwise struggle to attain due to entrenched gender biases and discriminatory practices.

By mandating a minimum representation of women in decision-making bodies, TSMs can help break the cycle of underrepresentation and challenge traditional power structures that perpetuate gender inequality. TSMs can be seen as catalyst for broader social change by increasing the visibility of women in leadership roles, challenging stereotypes, and inspiring future generations of women to engage in politics. While TSMs are temporary in nature they can have long lasting impacts.

Such gender-sensitives frameworks can help ensure that the rights and needs of all are addresses, thereby promoting equality and equal representation. By incorporating gender-sensitive provisions into electoral laws and regulations, such as measures to promote women’s participation and protects against gender-based violence, societies can create environments that facilitates the full and equal engagement of women and other marginalized groups in electoral processes.

See programmatic option “Support the design of gender-inclusive laws, policies and regulations”

Awareness raising campaigns, trainings and other forms of civic education can help debunk gendered myths and disinformation being spread offline and online, as well as foster other narratives that are positive towards women’s partaking in political life.

Online channels of communication can and have been abused, to serve as a means for perpetrating online forms of violence, including hate speech and harassment, at times leading to the instigation of real-world violence. These otherwise inclusionary tools can be used to scare women from participating in public life, including as candidates during electoral process, thereby degrading and jeopardizing gender equality. Online violence is marked by a greater number of spectators and hateful comments and attacks have proven difficult to remove. Insults, hate speech and rhetoric can remain online indefinitely, both creating longer lasting damage, but also leaving a trail back to their perpetrator.

By some measures, online attacks can be more vicious due to the anonymity and universality offered by the digital sphere. Online violence also suffers from a legal gap in many countries. Programmatic responses can include advocacy efforts and legal advice to close this gap. Gender-sensitive early warning and early response systems and hotlines can contribute to not only increased data on the scale of online violence against women, but also to facilitate response including psychosocial support for female victims.

can deter actors from gender-discriminatory behaviour and speech. Traditionally, Codes of Conduct have in many countries been set up to regulate the behaviour of various stakeholders during the electoral process, including political parties, the media, election observers and traditional leaders and other key actors, among others, contributing to setting ground rules for a conducive and peaceful electoral environment.

This has, in most cases, meant that the Although the overall aim of such Codes has been to promote peaceful elections, but the Code the Code itself might not have included specific provisions on gender-based harassment, intimidation, assault or gendered forms of violence. With more political parties expanding Zero Tolerance Codes of Conduct, condemning any forms of gender-based violence and harassment, it is becoming increasingly clear that Codes of Conducts can help promote a gender-sensitive working culture through, for example, promoting gender-sensitive language and sanction gender-discriminatory behaviour and speech.

A gender-responsive early warning system – which is also coupled with an early response system – can both serve the purpose of flagging imminent and emerging incidents and risks such as violence and strengthen collaboration between relevant of actors involved in relation to risks of violence and conflict. Early warning systems that are people-centred -; ensuring that appropriate, applicable, and timely early warnings also reach the most vulnerable, including women, – are the most effective ones and can be critical tools to use in electoral processes when assessing risks of violence and other threats, particularly against women. A gender-responsive early warning systems that also includes indicators with strong gender component can help identify such risks.

See programmatic option on “Gender-responsive early warning system coupled with early response”

The challenges, and opportunities presented by the era of digitalisation, increased use of technology and AI, have transformed electoral processes in every country, including in relation to inclusion and participation aspects. Democratic participation can flourish as a result of digital technology, allowing for increased awareness raising and information sharing, community building, data driven policy and programming and so forth. The rise and increasing use of AI Artificial Intelligence (AI) may have also played a role in what some have dubbed the reversal of gains towards gender equality, including but not limited to bias within technology contributing to the perpetuation of gender stereotypes and the exclusion, and manipulation for political or monetary gain. There are a number of activities electoral practitioners can engage in to better grasp the impact and use of technology and AI on the inclusion and exclusion of women in electoral processes including

We know that elections can lay bare existing tensions and conflicts in societies. In post-conflict societies they can serve as an important vehicle for channeling existing grievances and tensions in a constructive manner. However, they also have the potential to do the opposite. This is particularly the case in high stake elections, whereby the post electoral period can be viewed as a period in need of peacebuilding. Women can play a key role in such post-election reconciliation, by creating spaces where grievances can be channeled and discussions around ongoing tensions can be facilitated. By providing platforms for women, particularly women leaders to share their knowledge and expertise amongst themselves and other, it can help foster collaborative approaches and innovative solutions to conflict resolution and long-lasting peace. Such spaces will also help maintain critical partnerships that are especially important in post-conflict context, where women leaders often continue to play a key role in building trust in political processes and institutions, including electoral processes.

Ace Project: The Electoral Knowledge Network. Accessed here: https://aceproject.org/

Ballington, J., Bardall, G., & Borovsky, G. (2017). Preventing violence against women in elections: A programming guide. UN Women. Accessed here: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2017/11/preventing-violence-against-women-in-elections

Bardall, G., Bjarnegård, E., & Piscopo, J. M. (2020). How is political violence gendered? Disentangling motives, forms, and impacts. Political Studies, 68(4).

Birch, Sarah, Ursula Daxecker, and Kristine Höglund. “Electoral violence: An introduction.” Journal of Peace Research

Convention of the Elimination of all Form of Discrimination against Women. (1979) Access here: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/cedaw.pdf

Convention of the Political Rights of Women (1953). Access here: https://treaties.un.org/doc/treaties/1954/07/19540707%2000-40%20am/ch_xvi_1p.pdf

International IDEA, SAP International (2008). Women, Representation and Violence: Exploring Constituent Assembly Election in Nepal. Accessed here: https://iknowpolitics.org/en/learn/knowledge-resources/case-study/contesting-patriarchy-gender-gap-and-gender-based-violence

International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). Access here: https://www.ifes.org/

International Foundation for Electoral Systems (2016) “Violence Against Women in Elections: A framework for Assessment, Monitoring and Response”. Access here: https://www.ifes.org/publications/violence-against-women-elections-framework

Inter-Parliamentary Union (2021) Women in Politics: Map. Accessed here: https://www.ipu.org/women-in-politics-2021

Inter-Parlimentary Union, UN Women (2023) Women in Politics: Map. Accessed here: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/03/women-in-politics-map-2023

iKNOW Politics Network. Access here: https://iknowpolitics.org/en

iKNOW Politics (2019): “Summary of the e-discussion on Violence Against Women in Politics” Access here: https://iknowpolitics.org/en/learn/knowledge-resources/discussion-summaries/summary-e-discussion-violence-against-women-politic-0

iKnowPolitics, Parliaments & Representatives. Accessed here: https://iknowpolitics.org/en/focus-areas/6060

Krook, Mona Lena, and Juliana Restrepo Sanın (2016) “Violence against Women in Politics: A Defense of the Concept.”

Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences (2019). “Violence against women, its causes and consequences”. Access here: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g19/178/31/pdf/g1917831.pdf?token=VX6xSoJ3YszkWfxIGn&fe=true

Schneider, Paige and David Carroll (2020) “Conceptualizing more inclusive elections: violence against women in elections and gendered electoral violence.”

United Nations Department of Political Affairs (2016). “Preventing and Mitigating Election-related violence”. Access here:: https://dppa.un.org/sites/default/files/ead_pd_preventing_mitigating_election-related_violence_20160601_e.pdf

UNDP and UN Women (2016): “Inclusive Electoral Processes: A Guide for Electoral Management Bodies on Promoting Gender Equality and Women’s Participation”. Access here: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/democratic-governance/electoral_systemsandprocesses/guide-for-electoral-management-bodies-on-promoting-gender-equali.html

UNDP and UN Women (2017). “Preventing Violence against Women in Elections: A programming Guide.” Access here: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/VAWE-Prog_Guide_Summary-WEB.pdf

UNDP (2014): “Gender Equality in Public Administration.” Access here: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/democratic-governance/public_administration/gepa.html

UNDP (2022). Gender Equality Strategy 2022 – 2025. Access here: https://genderequalitystrategy.undp.org/?_gl=1*14rxuez*_ga*MTU2MTUyOTM4LjE2NTY0MTE0NjQ.*_ga_3W7LPK0WP1*MTcwNzI0NjkwMy4xNzIuMS4xNzA3MjQ5NDgyLjU3LjAuMA.

UNDP (2023). Gender Social Norms Index. Access here: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdp-document/gsni202303pdf.pdf

UNDP (2023). Strengthening women’s political participation: a snapshot of UNDP-supported projects across the globe. Access here: https://www.undp.org/publications/strengthening-womens-political-participation-snapshot-undp-supported-projects-across-globe

UNDP (2023) Supporting the Introduction of Temporary Special Measures: Guidance for UNDP Country Offices. Accessed here: https://www.undp.org/governance/publications/supporting-introduction-temporary-special-measures-tsms

UNDP (2023). “Building inclusive democracies: A guide to strengthening the participation of LGBTI+ persons in political and electoral processes.” Access here: https://www.undp.org/publications/building-inclusive-democracies-guide-strengthening-participation-lgbti-persons-political-and-electoral-processes

UNDP Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed here: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality

UNDP “Women’s Political Participation”. Accessed here: https://www.undp.org/governance/womens-political-participation

UN Gender Portal. Accessed here: https://genderquota.org/

United Nations (2005): “Women and elections. Guide to promoting the participation of women in elections.” Accessed here: http://iknowpolitics.org/en/knowledge-library/guide-training-material/women-elections-guide-promoting-participation-women

UN Women. Political Participation of Women. Access here: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/focus-areas/governance/political-participation-of-women

UN Women, OHCHR and SRVAW (2018): “Violence Against Women in Politics: Expert Group Meeting Report and Recommendations”, 8-9 March 2018, New York. Access here: http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2018/9/egm-report-violence-against-women-in-politics

Electoral assistance: Electoral assistance can be defined as the legal, technical and logistic support provided to electoral laws, processes and institutions.

Electoral cycle: The electoral cycle covers pre-electoral period, electoral period, and post-electoral period. The approach taken by UNDP includes emphasis on long-term activities and increasing the capacities to support inclusive political participation.

Election related violence is understood as a form of political violence, “which is often designed to influence an electoral outcome and therefore the distribution of political power”.

Gender can be understood as “the roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that a given society at a given time considers appropriate for men and women.” These realities are socially constructed and learned through socialization. They are context and time specific and are subject to change. Although traditional forms of gender identity are based on the binary categorization of men and women, gender realities are diverse and fluid, constantly evolving, and the binary logic might restrict freedom and possibilities of human beings, especially for transgender, intersex and gender non-conforming people.

Gender balance refers to the participation of an approximately equal number of women and men within an activity or organization. Examples are representation in committees, decision-making structures or staffing levels between women and men.

Gender-based violence refers to violence directed against a person because of his or her role in a society or culture.

Gender equality means equal opportunities, rights and responsibilities for women and men, girls and boys. Equality does not mean that women and men are the same but that women’s and men’s opportunities, rights and responsibilities do not depend on whether they are born or they identify themselves as female or male. It implies that the interests, needs and priorities of both women and men are taken into consideration.

Gender mainstreaming is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policy or programs, in all areas and at all levels. Gender mainstreaming in EMBs ensures that women’s and men’s concerns, needs and experiences are taken fully into account in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of all activities. Through this process, the EMB seeks to reduce the gaps in development opportunities between women and men and work towards equality between them as an integral part of the organization’s strategy, policies and operations, and the focus of continued efforts to achieve excellence. The term “gender integration” is also used in some contexts.

Gender-specific or gender-targeted interventions seek to tackle specific areas where women are unrepresented or disadvantaged, including through the adoption of TSM, and are part of a comprehensive gender mainstreaming approach.

Sex-disaggregated data are collected and tabulated separately for women and men. They allow for the measurement of differences between women and men on various social and economic dimensions.

Violence against women in politics (VAWP) is a form of discrimination, a human rights violation, and a challenge to democracy. VAWP affects women engaged in formal politics and women across public life, including women activists, journalists, and human rights defenders. VAWP includes cyberviolence, gendered disinformation, hate speech, and trolling and is often used to delegitimize the assertion of women’s rights. Violence, as both threat and lived experience, deters women, especially young women, from participating in politics and is a formidable obstacle to advancing women’s political participation.1

Political participation: Political participation more specifically, includes “a broad range of activities through which people develop and express their opinions on their society and how it is governed, and try to take part in and shape the decisions that affect their lives.

This document intends to provide an introductory overview of the topic. It should not be considered a policy document. It will propose parameters for study, define key terms and outline a provisional framework. Its audience shall be participants from a variety of organizations, including from the Global Working Group and participants of the regional consultative sessions who shall come from a variety of organizations and backgrounds.

For more informations contact : [email protected]

follow us on Twitter

Despite certain setbacks, there has been considerable progress globally in women’s political participation in the past two decades.

Today more women than ever before hold public office and engage in electoral processes in several capacities, including as staff, voters, candidates, or campaigners.

Yet, numerous challenges continue to negatively impact, halter or even prevent women’s meaningful partaking in public and political life, ; the most alarming factor being the perceived increase in violence against women in politics and electoral processes.

Increased gender-based violence in electoral cycles is taking various forms, ranging from harassment, intimidation, and sexual and physical violence against women in public life, including online; gender-biased scrutiny by media and the public; targeted attacks against female voters, at times resulting in women’s exclusion from electoral processes; to forced resignations and assassinations of women politicians in the most extreme cases.

Newly released global data from the 2023 UNDP Gender Social Norms Index also shows that nearly half of all people believe that men make better political leaders than women do, pointing towards tenuous progress in changing persistent biases against women’s full and active political participation

Considering the above-mentioned challenges and complex landscape, this report seeks to gain a better understanding of current trends, challenges but also opportunities to bolster gender-responsive electoral programming and guide electoral practitioners in their endeavors to strengthen women’s equal participation in elections in all their diversity. In aid of that, a thorough research process has been conducted through several channels, including desk and literature review, surveys, expert meetings and a series of regional consultations with practitioners working at country and regional level, which have all guided the report’s analysis.

There is no one-size-fits-all-approach available to tackle gender-based violence

A multipronged approach is critical when addressing matters related to violence prevention with sustained and targeted interventions in place before, during and after elections are held.

A range of activities are required to tackle the issues at hand

which all need to be tailored to the specific context it will be implemented in. In light of that, a thorough gender analysis that can identify women’s unique needs should be conducted in every electoral context before implementing any activity, programme or intervention.

To tackle the root causes of violence against women during electoral cycles

thorough assessment and analysis of pertaining social and cultural norms are critical starting points to better outline tailored programmatic approaches. A social norms assessment is a helpful starting point for electoral practitioners to conduct to identify both harmful and positive social norms in the context they are working in.

Temporary Special Measures (TSMs) have proven to be effective methods

to enhance women’s political participation and contribute to positive social norms change. Successful implementation must, however, be based on wider acceptance of such measures in a society. Fostering an enabling environment for TSMs requires long-term advocacy campaigns and awareness raising and needs to involve several actors jointly, including Electoral Management Bodies, international organizations, civil society and the media.

Supporting the design of gender-inclusive laws, policies and regulations

more generally will lay the groundwork for meaningful participation in all aspects of an electoral process. This should be a priority for electoral programmes and for practitioners and must be coupled with protocols, procedures and training to ensure implementation.The need to involve men and boys in this work is also critical

particularly to better challenge norms of violent masculinities that can lead to and legitimize violent behaviors. For such efforts, a number of interventions are available and should, preferably, be introduced at the same time, including awareness-raising campaigns, trainings and educational efforts. Other, more innovative approaches can also be explored, such as the use of virtual reality to foster inclusive behaviour and, in turn, a culture of non-violence that can challenge attitudes justifying violence.

The challenges, and opportunities presented by the era of digitalisation have transformed electoral processes in every country

including in relation to inclusion and participation aspects. Democratic participation can flourish as a result of digital technology, allowing for increased awareness raising and information sharing, community building, data driven policy and programming and so forth. Expression in the online space is, however, not guaranteed for all, if not undermined for some. Of particular worry is the rise of online violence against women, which has become an endemic concern within elections, deployed to make public life untenable for aspiring female politicians and supporters.

Gender responsive early warning and early response systems and GBV hotlines are ways in which reporting can increase and the impunity gap can be addressed. Offering psychological support to female candidates who are ate heightened risks of experiencing violence during times of elections can also be ensured through such hotlines. Engagement with political parties to set up Zero Tolerance Codes of Conduct are another avenue.

The programmatic option “Support gender-sensitive design of technology and AI” contains several activities electoral practitioners can engage in to better grasp and respond to the impact of technology and AI on the inclusion and exclusion of women in electoral processes.

Women play a pivotal role in sustaining peace during electoral process

including through dialogue and post-electoral reconciliation efforts. Today we also know that gender equality is the number one predicament of peace. In light of that, the need to support intersectional spaces where women – ranging from women community leaders to women wings of political parties– can engage amongst themselves and others to build consensus and the foundations of long-term inclusive governance and peace is key.Gender-proofing electoral processes

such as including flexible polling hours and illiterate friendly voting booths, are concrete actions that can ensure electoral processes are gender-sensitive. Working with national security forces to ensure adequate measures to ensure women’s safety are being taken into consideration is also key to ensure electoral processes responds to women’s unique needs.