UN electoral assistance is provided to Member States at their request or based on mandates from the UN Security Council or General Assembly only. The UN system-wide focal point for electoral assistance matters, the Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, decides on the parameters of such assistance, based on needs assessments led by the Electoral Assistance Division of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA). Implementation is guided by UN electoral policies set by the Focal Point, in consultation with UN entities, including UNDP.

Participation as a pillar of the UN Security Council resolution 2250 (2015) relates to taking young people’s participation and views into account in decision-making processes, from negotiation and prevention of violence to peace agreements and electoral processes. Youth participation is also an opportunity to deliver on the promises of inclusive electoral processes, and thereby, give voice to people from excluded groups.

Participation is a key component of any quality stakeholder engagement and includes access to information and influence in decision-making, and for youth participation, this includes influence in decision-making on all issue areas and not only youth-specific matters. Other relevant components of youth participation are empowerment, learning and life skills, and access to rights. Political participation, more specifically, includes “a broad range of activities through which people develop and express their opinions on the world and how it is governed, and try to take part in and shape the decisions that affect their lives.”

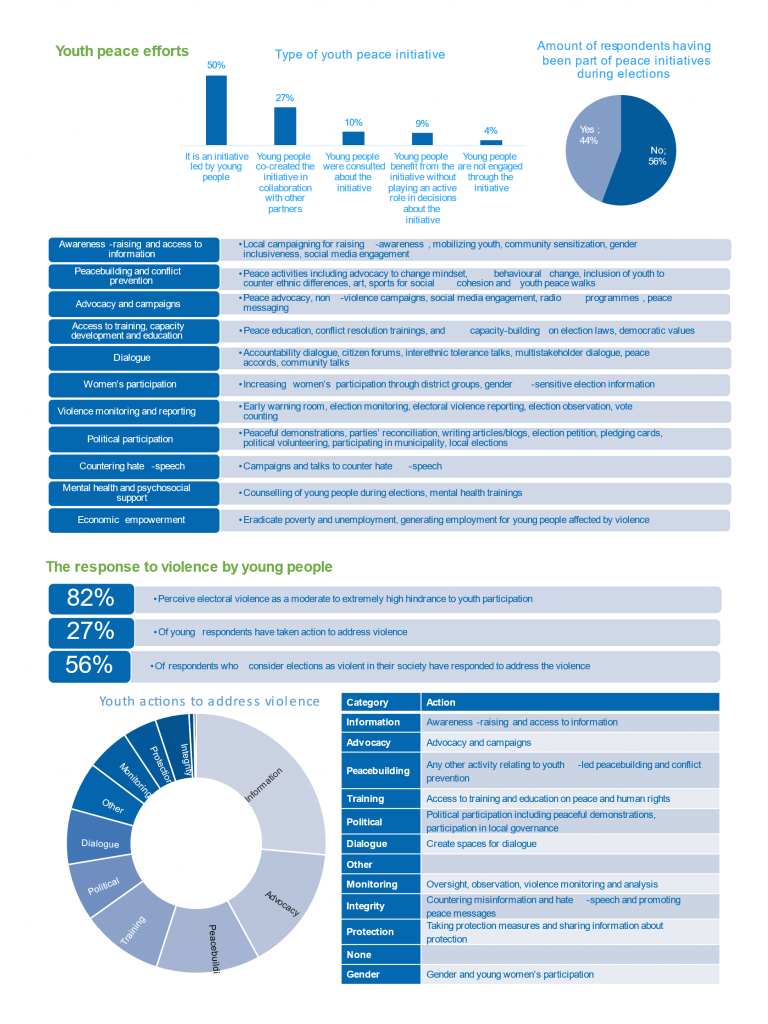

Young people often act for peace in their communities, hold political leaders to account for climate promises and deliver relief to the most vulnerable people, among other areas of action. However, there is low youth participation in formal politics in many societies. Young people and their organizations, movements and networks are more likely to engage through informal processes and alternate spaces. Formal participation can be understood as engagement in established processes or institutions, whereas informal participation refers to people’s organization for political, social or economic aims outside the realm of political parties and formal institutions. In order to understand youth leadership and agency during elections, it is important to consider these alternative forms of participation such as youth civic activism and social movements, and that non-participation is also a form of participation/political expression. The youth survey and consultations of this research process have been a testimony to this.

Young people are not a homogeneous group, and electoral-related programmes would benefit from considering how the various identities of young people intersect and the impact of this in specific contexts in order to promote the participation of young people in their diversity. Leaving no one behind is a principle for sustainable development. To leave no youth behind during the electoral process, stakeholder analyses should be sensitive to young people’s identities relating to class, caste, religious affiliation, tribe, ethnicity, gender, age, people with disabilities and rural/urban, among others.

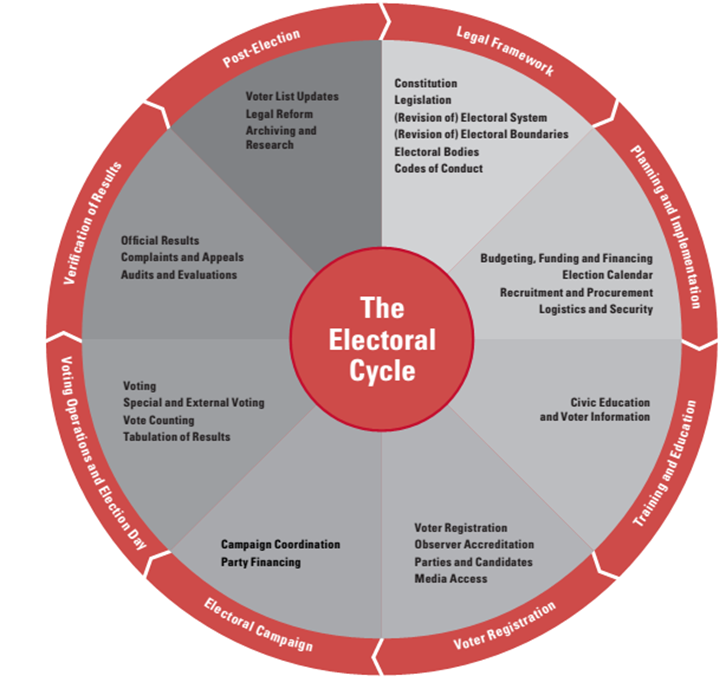

Youth participation is important and necessary throughout the electoral cycle. An electoral cycle approach “emphasizes the importance of long-term activities aimed at developing capacities for inclusive political participation. It covers the pre-electoral, electoral and post-electoral periods.” This can contribute towards fostering a safe, gender-responsive and enabling environment for youth participation where young people can raise their voices, engage in electoral operations and be agents for peaceful elections. It has become a key priority for the international community to not only amplify youth voices but to find ways to listen more attentively to youth perspectives.

This research report is among the deliverables of the youth participation workstream of the Sustaining Peace during Electoral Processes (SELECT) project. The research process was developed to deliver on the content of the project output 1 for the development of an online knowledge hub and to be used through the project output 2 for capacity-building and outreach. The research process has been designed to be inclusive and participatory to ensure the content produced in the final product has a multi-regional lens and takes into consideration experiences and knowledge from a wide range of stakeholders and particularly young people.

There are many forms and levels of youth participation: from informing young people about a matter, to empowering youth to take a final decision. Deliberative processes are a way of engaging citizens in policymaking, and youth deliberative participation can create space for intergenerational dialogue and for young people to have an influence upon decisions and conclusions relating to a set policy area. Furthermore, youth participation unfolds in both offline and online spaces and often by leveraging digital tools in combination with in-person activities. As will be elaborated below, online youth participation is integral to youth peace efforts during elections, but it comes with some specific opportunities and challenges.

Electoral assistance may want to consider the form, lens and level of participation that is the most relevant to the specific activity—and it will most likely include multiple levels—when deciding upon approaches to promote youth participation during elections.

Young people’s perspectives, needs and aspirations in the context of elections and sustaining peace are often overlooked.

All people have the right to participate in public affairs and all States are called upon to “promote and ensure the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for youth….” The United Nations is committed to supporting diverse and inclusive participation of young people among other specific population groups and is working to promote inclusive participation channels. Fostering a safe, gender-responsive and enabling environment is also a critical aspect of promoting youth participation in matters relating to peace and security.

This section introduces a range of areas that could be considered for the promotion of youth participation to sustain peace during elections. The areas were identified on the basis of the consultative process for the youth participation workstream of the Sustaining Peace during Electoral Processes (SELECT) project and are by no means exhaustive.

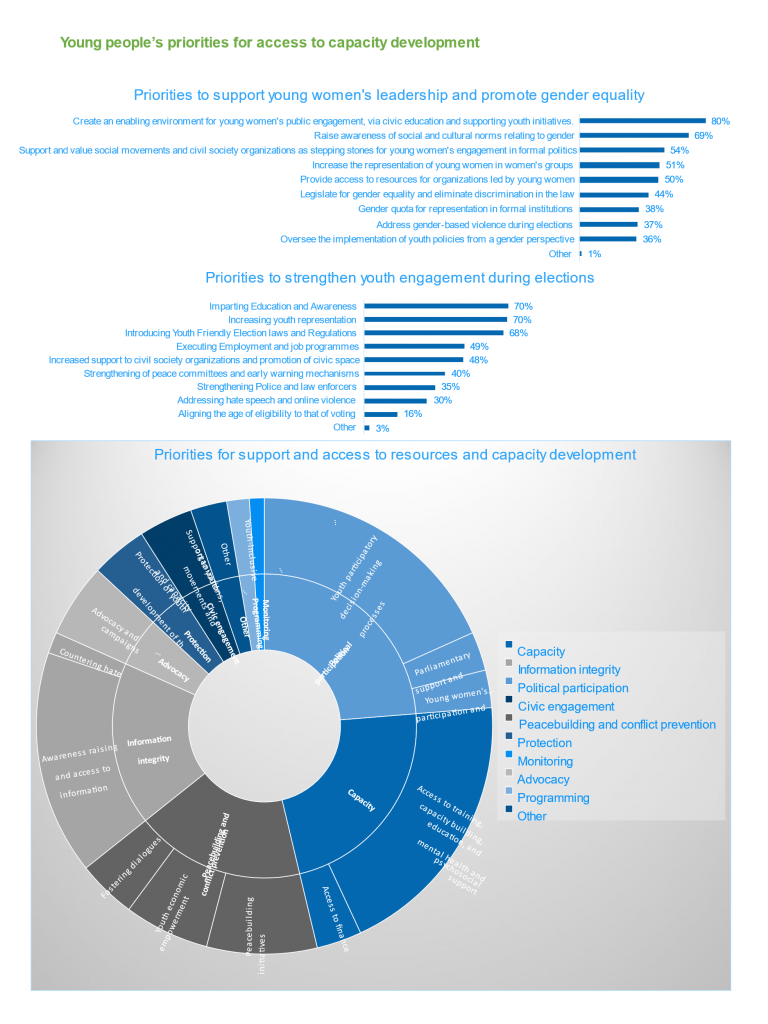

The consultations, youth survey and research conducted through the SELECT youth participation workstream have identified opportunities and challenges for electoral-related programming involving youth including programmatic entry points for the promotion of youth participation to sustain peace during elections.

Among the findings was the importance of working with young people throughout the programming cycle—from the design phase to the implementation and evaluation phases—as well as throughout the electoral cycle because young people play a key role in the prevention of violence and conflict, sustaining the conducive environment for peaceful elections and the bridging of potential divides in the pre- and post-electoral periods.

Applying an integrated approach to the prevention of electoral-related violence through the creation of synergies between programmes on elections, youth empowerment, inclusive governance and peacebuilding deserves consideration.

Electoral-related programmes can promote youth participation at different levels and degrees. For instance, some programmes may adopt a youth-inclusive approach, which relates to young people having the right to engage throughout the programme cycle whereby their perspectives are taken into account. Other programmes may adopt a youth-sensitive approach, meaning that initiatives respond to, and are based on, the realities, needs and aspirations of young people.

Quality assessments and analyses provide the starting point for programming to effectively promote youth participation. Therefore, increased attention may be given to conducting youth-inclusive and youth-sensitive needs assessments and conflict analysis to inform programming relating to electoral violence prevention with the aim of understanding the lived experiences of young people, the challenges they face and the opportunities for peace they identify, while considering youth in its diversity.

These assessments may form part of a larger assessment and/or analysis or may be specifically conducted to inform inclusive programming around elections.

The following recommendations are suggested as entry points for strengthening the capacity of electoral-related programmes to work with and for young people.

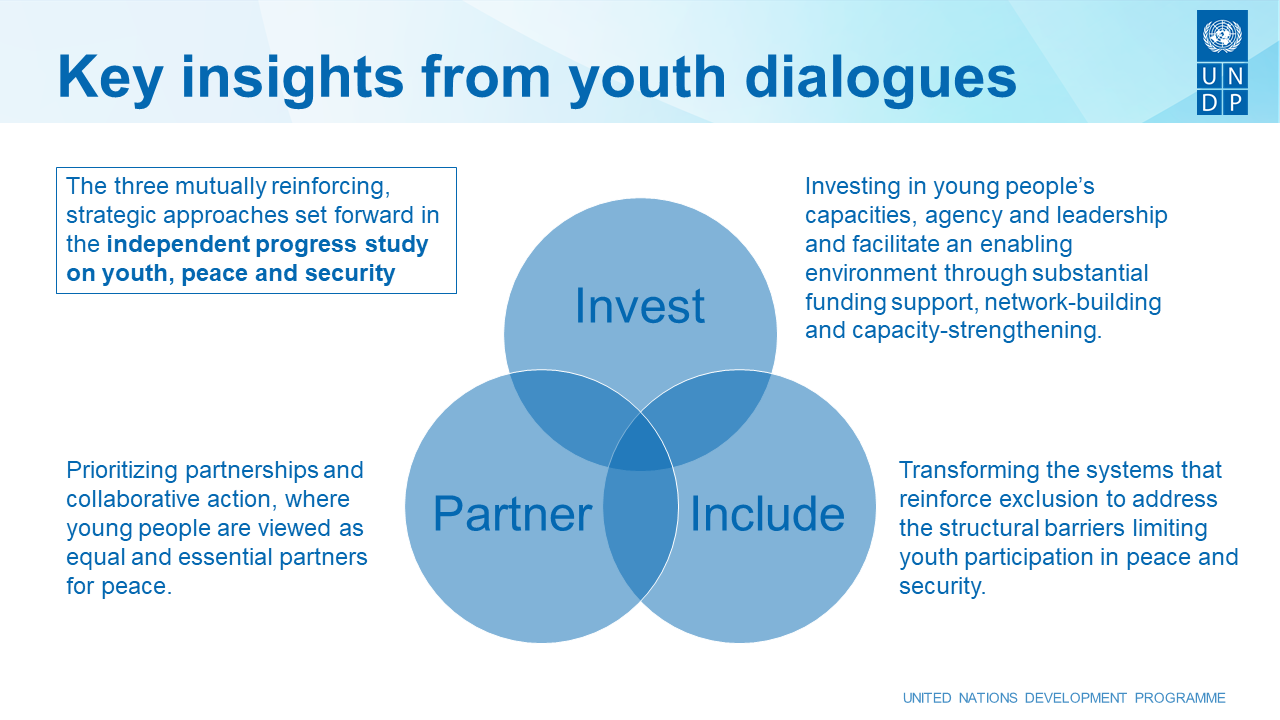

The recommendations are structured around a slightly modified version of the three mutually reinforcing strategies set forward by the independent progress study on youth, peace and security.

into civic and voter education, considering both formal and non-formal education incorporating the political, civic, cultural and socioeconomic issues affecting the situation of youth.

to address all forms of violence—and particularly gender-based violence—during the electoral cycle. This entails understanding the varying and intersecting identities of young people and how stigma, discrimination and violence may be experienced as a result of this.

Electoral-related programmes may support youth-driven efforts in communities by:

For more informations contact : [email protected]

follow us on Twitter

can promote youth participation to sustain peace at different levels and degrees.

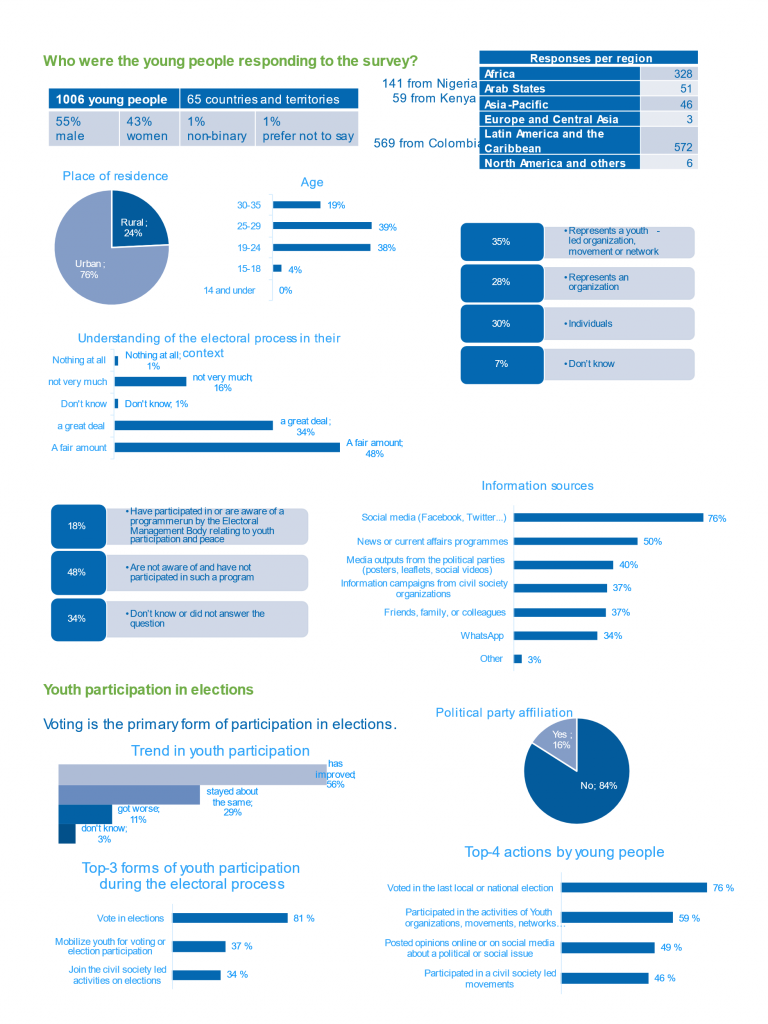

The purpose of this report is to lay out challenges and opportunities for electoral-related programming involving youth, with a specific focus on programmatic entry points for the promotion of youth participation to sustain peace during electoral processes. The findings have been informed by an extensive consultative process, including regionally focused and youth specific consultations and a youth survey with over 1000 responses, alongside a literature review to assess the current state of play in terms of policies and research that informs programming.

Invest in youth leadership and agency and an enabling environment

electoral-related programmes can consider supporting youth-led peace efforts in communities such as theaters for peace, dialogue meetings, awareness-raising through social media and radio programmes about electoral processes, rights and non-violence, among others.

Include youth by transforming systems and removing structural barriers

electoral-related programmes can consider opening avenues for youth participation in decision-making processes through youth-friendly policies, enhancing transparency and accountability of institutions and addressing social and cultural norms relating to gender and age that may create a barrier for the implementation of legislation and policies relating to youth participation during elections, among others.Partner with young people and their organizations movements and initiatives

electoral-related programmes can create space for intergenerational dialogue on electoral issues and violence prevention, support engagement mechanisms such as youth councils/caucuses/platforms and include young people in the design of electoral-related programmes..